Editor’s Note: This article on Artis Avis, a planned steam flying machine, was written by Andy Johnson for the newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Eastern Pennsylvania in 2007. Mr. Johnson has graciously allowed this article to be reproduced here in its entirety. If you enjoy this article, please check out the author’s web site on Benning’s Brigade, Field’s Division, First Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, A Not So Brief History of Benning’s Brigade. Mr. Johnson is preparing a manuscript for this unit and hopes to turn it into a book someday soon.

The “Great Steam Duck,” Artis Avis, and a Nineteenth Century Con Man1

by Andy Johnson

By March of 1865, the southern Confederacy was near collapse. Georgia and South Carolina were devastated, Sherman had moved into North Carolina, and separate raids threatened heretofore unscathed regions of Mississippi and Alabama. The damage showed in the Confederacy’s armies– the only cohesive bodies of troops left were Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, Kirby Smith’s in the trans-Mississippi, and the shadow of the Army of Tennessee, regrouping under Johnston in North Carolina.

Lee’s army first engaged Grant at Petersburg on June 18, 1864. Grant’s ongoing efforts to cut Lee’s army off from supplies had led to a series of dynamic, violent clashes aimed beyond the armies’ defensive lines. While few of Grant’s individual offensives had been successful, they were collectively eroding Lee’s army and its ability to maintain the contest. Nine months of this action had stretched the opposing lines from the Chickahominy River, south across the James River to Bermuda Hundred, then across the Appomattox River to Petersburg, before turning west and extending beyond Hatcher’s Run.

The entrenched lines stretched well over thirty miles. More impressive than their length was their construction. On the line between the James and Chickahominy Rivers, the opposing entrenched picket lines were separated by 1 ½ to 2 miles, both sides covering their picket lines with abatis. Behind the pickets, the Confederates’ main defensive line featured a cleared field of fire 1,000 yards deep. Any attacks would need to traverse two exposed lines of abatis and, just outside the works, mine fields forty feet in depth. These extensive, layered defenses secured the Confederate lines, despite a manpower shortage that allowed only one soldier per five feet of line.

The final, deepest portion of the Confederate defensive line was rarely mentioned in reports or letters home. A second picket line of soldiers, specially chosen for their perceived fidelity, was placed in rear of the main defensive line and charged with deterring and/or catching deserters. A long record of success against northern armies was outweighed in many soldiers’ minds by shoddy uniforms, limited rations, and horror stories of Yankee depredations at home. Even the Confederate government sent mixed messages – while the Congress passed measures to raise 200,000 black troops and give Lee supreme command of the military, a delegation led by Vice President Alexander Stephens attempted to negotiate a peace settlement.

Many of Lee’s soldiers anticipated that he would abandon Richmond and attempt to join forces with Joseph Johnston in North Carolina. As Lee prepared to attempt just such a move, he was counseled by James Longstreet, “It will be a grievous thing to be obliged to abandon our position…but it would be more grievous to lose our army,” though, owing to the poor state of the army’s transportation, “We shall lose more men by a move than by a battle.” The approach of Phil Sheridan and 10,000 cavalrymen from the Shenandoah Valley in early March only added pressure, and Longstreet’s corps, posted between James and Chickahominy, was placed under arms on March 13.

In this dark hour, a would-be savior appeared in the Confederate camps with an invention that could save the Confederate cause, or, failing in that, at least make him wealthy. Richard Oglesby Davidson was 58 years old, and described himself as an inventor. Two days after preparing to face Sheridan’s men, Private Arthur Benjamin Simms, a soldier in Bryan’s Brigade, Kershaw’s Division (formerly Semmes’s, of McLaws’s) wrote his sister, “I heard a man make a speech today soliciting contributions in favor of an invention he terms Artis-avis or the Bird of Art. He proposes to make one of these Birds of twenty thousand dollars, if this one is a success, why, then the Government will give him ample means to make several hundred. His Bird is modeled in shape after other birds and will be about fifteen feet long and proportioned accordingly. He intends its motion to be similar to that of a bird, his wings to raise him and give him his forward motion, his tail to act as a rudder to steer and direct his course.”

Davidson made his pitch to most of the brigades in Longstreet’s and Hill’s corps, leaving a trail of corroborating accounts. Artis Avis was to be built of hoop iron, covered with white oak, and powered by a small steam engine. A foot activated spring would allow the pilot to open a trapdoor through the bottom of the “car,” and drop individual artillery shells onto the enemy below. Davidson claimed to have a functional prototype; a veteran recalled “he wanted to sail over the Yankee camps some dark night, blow fire out of the mouth of this monster bird, and from a trapdoor drop shells in the Yankee camps, and thus stampede the Yankee army. With this monster bird, he could sink every Yankee gunboat on the James River.”

Colonel Asbury Coward, a Citadel graduate and commander of the 5th South Carolina Infantry, Field’s (formerly Hood’s) Division, recalled Davidson’s presentation of “A miraculous invention based on the mechanism of bird flight…As an example he used the flight of the wild duck.” Coward skeptically noted that Davidson had only the vaguest of answers to his detailed questions, particularly about the power capacity of the steam engine and its ability to actually lift the device. When pressed, Davidson resorted to obfuscation, claiming that the mechanical action of the device emulated the motions of a bird. While the wings flapped, the “The stretching out and retraction of the neck overtipped this [gravity’s] balance…the result was forward motion.” Davidson offered to describe the operation of Artis Avis to Coward in detail, in the privacy of Coward’s tent, should the Colonel only subscribe funds.

Davidson had been trying to fund his invention since 1861, when he “sent a memorial to the Provisional [Confederate] Congress, then in session at Montgomery, asking assistance in behalf of my invention, with the view of employing it against our enemies…At a subsequent period a similar application was presented to that body, then assembled in [Richmond]…At a later period still another memorial was handed to a member of the House of Representatives of the Confederate States Congress, but which never was presented to that body.”

By January 1864, Davidson was reduced to appealing to the Quartermaster General’s Office of the Confederate Army, and to the public at large through newspapers. Attempting to capture the imagination of the masses, Davidson published an article in the Richmond Daily Dispatch that Billy Mitchell would have been proud to claim: “let it be supposed that…1,000 of these Birds of Art were stationed at a point five miles distant from a hostile military camp, fortification, or fleet of war vessels; that each Artisavis was supplied with a fifty pound explosive shell, and being started singly, or two or three abreast, going out and dropping those destructive missiles from a point of elevation beyond the reach of the enemy’s guns, then returning to the place of departure and reloading, and thus continuing the movement at the rate of 100 miles per hour. It will be seen that within the period of twelve hours, one hundred and fifty thousand death dealing bombs, could be thus thrown down upon the foe, a force that no defensive art on land, however solid, could withstand even for a single day; while exposed armies and ships would be almost instantly destroyed, without the least chance of escape.”

The theme of the article was repeated a year later to Davidson’s final audiences, the soldiers, with further elaboration on “how easy it would be to destroy a City by carrying Greek fire and dropping [it]…we could…burn all the principal towns and cities of Yankeedom…This Bird, he says should more properly be termed Bird of Peace, because he intends that every nation shall be furnished with them and they are so destructive that nations will prefer the settlement of all difficulties by Diplomacy rather than war.”

Davidson had a history as an “aeronautical engineer,” using the terms loosely, a history that far predated the war, a history he avoided. In 1840, he published a Disclosure of the Discovery and Invention, and a Description of the Plan of Construction and Mode of Operation of the Aerostat: or a New Mode of Aerostation. Davidson’s “Aerostat” invention was a “flapping wing machine,” patterned after the American eagle, with an attached hot air balloon. The balloon would lift a “car,” and an operator, seated in the car, would manually flap the attached wings to manage the contraption’s descent.

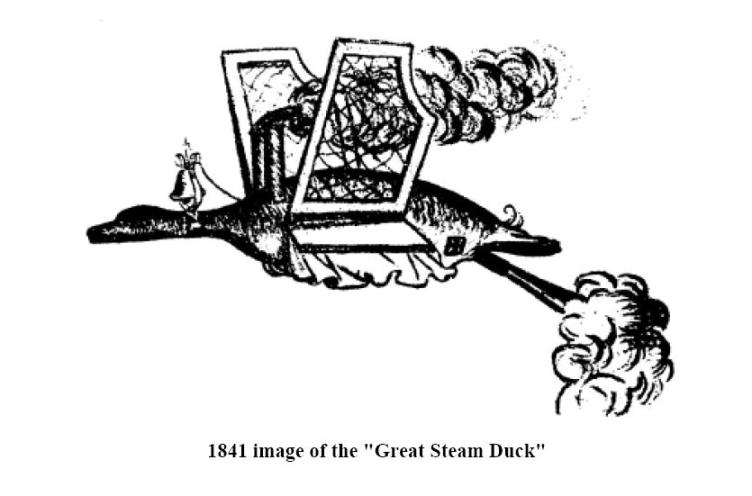

In response to Davidson’s “invention,” an anonymous “Member of the L.L.B.B.” (Louisville, Kentucky, Literary Brass Band) published a small book, The Great Steam Duck: Or A Concise Description of a Most Useful and Extraordinary Invention for Aerial Navigation. The Steam Duck opened by pointing out an 1833 publication authored by H. Straight, of New York, describing an invention nearly identical to Davidson’s, whose 1840 publication thus represented neither a “discovery” nor anything “new.” The author panned Straight’s/Davidson’s entire concept as impractical, then proceeded to describe a superior flying machine, a “flying duck,” measuring fifteen feet by six feet. The cabin of the Duck would be constructed of a hickory frame, covered in canvas; the wings of whalebone and silk; a steam engine, located in the craw of the beast, powered the wings; and a “scap pipe” was located under the duck’s tail. After describing the design of the “Steam Duck” in explicit detail, the author disavowed the plan and grouped the whole notion with Davidson’s work as impractical fakes. The author had some idea of the many technical advances required before powered, manned flight could be realized.

Wartime descriptions leave little doubt that “Artis Avis” was merely the “Great Steam Duck,” presented as a farce twenty years earlier, with a few cosmetic changes and a trapdoor. Colonel Coward wasn’t the only skeptic; Simms concluded, “I should as soon look for perpetual motion to be invented as for one of Davidson’s birds to rise and fly…I never gave him anything, he received from the Brigade one hundred and twenty seven dollars – pretty liberal patronage for a humbug.” Another soldier’s reminiscence provides insight into the minds of the hundreds of Confederate soldiers who fell prey to Davidson’s presentations: “I didn’t have any money to give, but I was sure anxious to see that man stampede the Yankee army.”

Needless to say, no Federal forces were bombarded by aerial vehicles in 1865. Whatever miniscule chance there was of that happening vanished as Grant’s final, and most successful, offensive opened on March 29, 1865. It took another fifty years – and several technical leaps, as foreseen in 1840 – before flying machines capable of carrying people and dropping bombs were sufficiently refined for use.

This article was originally published in the newsletter of the Civil War Round Table of Eastern Pennsylvania in 2007, and as such was not footnoted. Students of the topic and Civil War will recognize most of the period quotes. I cannot share this with a broader audience without recognizing Faith K. Pizor’s “The Great Steam Duck,” found in Technology and Culture, Volume 9, Number 1, January 1968, pp. 86-89, as the source of the information on Davidson’s pre-war “inventiveness.”

- Original material copyright 2007, 2011 Andrew Johnson. All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced without the written consent of the author and is used here with permission. ↩