GORDON’S ATTACK AT FORT STEDMAN.1

BY GEORGE L. KILMER, COMPANY I, 14TH NEW YORK HEAVY ARTILLERY.

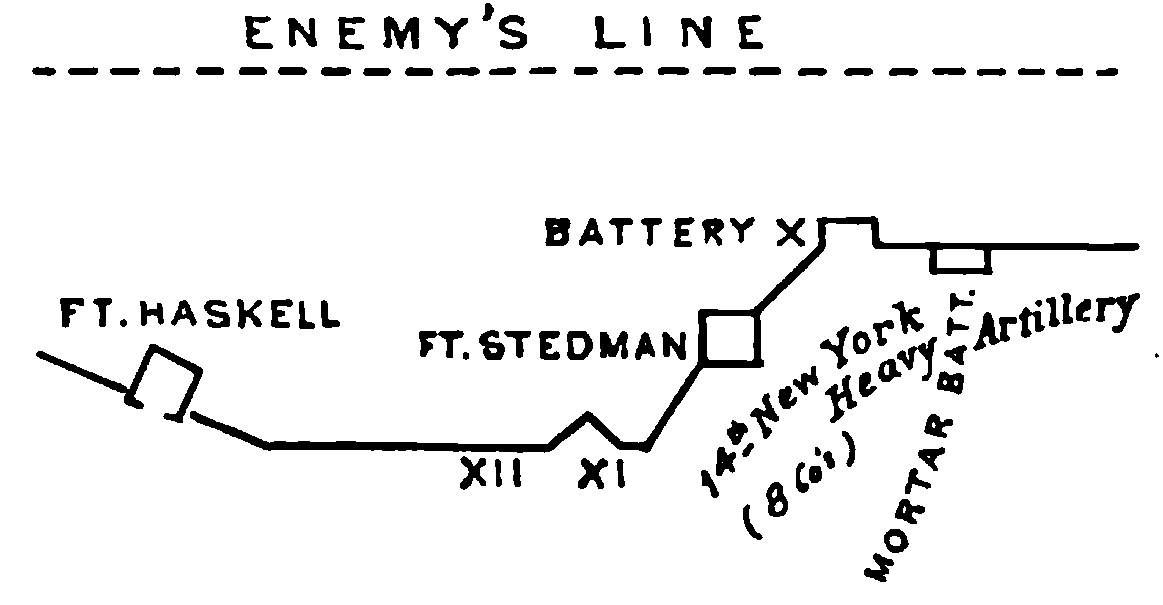

On the 25th of March, 1865, General O. B. Willcox’s division, of the Ninth Corps, was formed on the Petersburg lines in the following order from right to left [see map, p. 538]: Second Brigade (Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Ely), from the Appomattox to Battery IX, near the City Point Railroad; Third Brigade(1) (Colonel N. B. McLaughlen), from Battery IX to Fort Haskell; First Brigade (Colonel Samuel Harriman), from Fort Haskell to Fort Morton, directly facing Cemetery Hill. Fort Morton was a bastioned work, high and impregnable. Fort Haskell, the next down the line, on lower ground and quite under the best guns that Lee had on the crest, was a small field redoubt mounting six rifled guns and holding a feeble infantry gar-

***

(1) The Third Brigade was formed on the lines as follows: Eight companies of the 14th New York Heavy Artillery garrisoned Fort Stedman and Battery X, and guarded the trenches from the fort to a point one hundred yards to the right of the battery, and the 57th Massachusetts occupied the trenches on the right of the 14th; a detachment of Company K, 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, served a Coehorn mortar-battery near Battery X, and one section of the 14th Massachusetts Battery, Light Artillery, was stationed in the battery. Two sections of the 19th New York Battery occupied Fort Stedman. The 29th and 59th Massachusetts garrisoned the trenches and occupied Batteries XI and XII, where, also, Company L, 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery served, with batteries of 8-inch and Coehorn mortars. The 100th Pennsylvania occupied the trenches from Battery XII to Fort Haskell, and the 3d Maryland those for a short distance on the left of that work. The garrison of Fort Haskell consisted of four companies (I, K, L, and M) of the 14th New York Heavy Artillery, Captain Christian Woerner’s 3d New Jersey Battery, and a detachment of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery with Coehorn mortars.— G. L. K.

***

rison. Eighty rods farther was Fort Stedman, a stronger work than Haskell, and not so well commanded from Cemetery Hill. Two hundred rods from Stedman was Fort McGilvery, near the river and out of range of Lee’s heavy ordnance. In front of Haskell there were woods, marshes, and a sluggish stream completely obstructing the passage of men and guns from the enemy’s works eastward, but at Stedman, where the lines were but forty rods apart, the ground of both lines and all between was solid, and feasible for rapid movements of bodies of every arm of service, even to cavalry, and so here was a road that a master-stroke might open.

The headquarters of the 14th were at Stedman, where our acting colonel, Major George M. Randall, had command. Captain Charles H. Houghton, of Company L, commanded at Fort Haskell.

About 3 o’clock on the morning of March 25th Lieutenants C. A. Lochbrunuer and Frank M. Thomson, who were on night duty at Fort Stedman, informed Major Randall of an unusual commotion in front of the works. Lieutenant Thomson was directed to arouse the command at once and have the men moved to the works as quickly and as quietly as possible. The attack fell first upon Battery X and the breastworks on the right of it, and at that time the most of the officers and men of the garrison were in their places. Captain J. P. Cleary, Lieutenant Thomson, and Sergeant John Delack (who had been on guard duty during the night) had hauled a gun to the sally-port on the face of the fort toward Battery X, and it was opened upon the assailants. Many of the Confederates were captured and sent to the rear. (1) The guns on this face were fired several times under command of the officers of the battery. The artillerymen in Battery X attempted to defend their guns, and Lieutenant E. B. Nye, commanding the section, was shot down beside his pieces.

A second attack was immediately made on the rear of Fort Stedman by an overwhelming force that entered the breach at Battery X. The Confederates climbed over the parapets and in at the embrasures, and it was so dark that the garrison could not distinguish their own men from the enemy. Finding it impossible to hold the fort, the officers and men of the garrison who could get away took shelter on the outside of the parapets, and continued the fight with muskets. After daylight some of the officers and men of the 14th made their way along the moat of the trenches to Fort Haskell, and others fell back in line down the road toward Meade’s Station, and formed on the slope within rifle range of their old works. Major Randall was captured just outside of Fort

Stedman, but managed to get away from his captors and reach Fort Haskell. The Confederates had silenced the pickets in front of Fort Stedman by taking advantage of General Grant’s order of amnesty to deserters from the enemy. This order encouraged these deserters to bring in their arms, by offering payment for them. (2) On this occasion Confederates claiming to be deserters came in in large numbers, and very soon overpowered the pickets and passed on to the first line of works.

It was the intention of the Confederates to surprise Fort Haskell also. (3) This work was guarded by two rows of abatis, and at the gap where the pickets filed out and in a sentinel was on duty all night. The man who served the last watch that morning on this outer post was Sylvester E. Hough, Company M, 14th Regiment, and soon after he went on post (at 3 o’clock) he saw blue-lights flash up along the picket-pits. He also heard the sound of chopping at the abatis on the lines between Stedman and the Confederate works on its front. He hallooed to the second sentinel at Haskell, whose post was at the bridge across the moat, and an alarm was called out in the fort. Hough then advanced down the picket trail toward the outposts, and as he did so the first cannon was fired from Stedman, and the muffled sounds of the fighting there were heard.

There was a long slope between Fort Haskell and the picket-pits, and on this slope Hough met a column of men moving stealthily up toward our western front. The enemy were in two ranks, and had filed into our lines through the gap in front of Stedman, and were moving upon us unopposed, for they were between us and our pickets. If some traitor had divulged their secret movement hours in advance the men of this column could not have been at greater disadvantage than they now were by the chances of war. Hough, unseen by the enemy, ran back to the fort to advise the gunners. Three howitzers, double-shotted with grape, were trained upon the ground. The garrison had been called to arms, and the firing at Fort Stedman aroused the cry on all sides, “They have taken Fort Stedman.” The story told by Hough confirmed our suspicions that we were to be attacked, also; we had not long to wait. When the assailants neared the abatis we could hear their tread and their suppressed tones. “Wait,” said Captain Houghton; “wait till you see them, then fire.” A breath seemed an age, for we knew nothing of the numbers before us. Finally, the Confederate leader called out, “Steady! We’ll have their works. Steady, my men!” Our nerves rebelled, and like a flash the thought passed along the parapet, “Now!” Not a word was spoken, but in

***

(1) The flag of the 20th South Carolina was taken by one of the men of the 14th, and delivered to Major Randall.— G. L. K.

(2) Copies of the order referred to had been distributed in quantities, inside of the Confederate lines, during the autumn previous, and had the effect of inducing deserters to plan to get away in squads. My diary states that on the night of February 24th nine deserters came in on our brigade front, and 0n the next night fourteen, including a commissioned officer, many of them fully armed and equipped.— G. L. K.

(3) The Reverend Charles A. Mott. now (1888) pastor of the Calvary Baptist Church, Philadelphia, was a corporal in Company I, 14th Regiment, and had charge of a vidette picket-post on the right of Fort Haskell, on the night of the 24th and 25th. In a letter now in my possession, written November 1st, 1888, he states that at the opening of the attack a cannon-shot from Fort Stedman plowed the ground near his post, and very soon afterward he heard the tread of a column of the enemy advancing toward our lines.- G. L. K.

***

perfect concert the cannon and muskets were discharged upon the hapless band. It must have been a surprise for the surprisers, though fortunately for them we had been too hasty, and, as they were moving by the flank along our front, only the head of their column received the fire. But this repulse did not end it; the survivors closed up and tried it again. Then they divided into squads and moved on the flanks, keeping up the by-play until there were none left. Daylight soon gave us perfect aim, and their game was useless.

This stunning blow to the assailants in front of Haskell occurred just as another column of Confederates, that had filed into the works at Stedman, started on a rapid conquest along the trenches toward Fort McGilvery. We could see from Haskell the flashing of rifles as these men moved on and on through the camps of the parapet guards. Another column started also from Stedman along the breastworks linking our two forts. This division aimed to take Haskell in the right rear. At the very outset, this last movement met with a momentary check, for it fell upon two concealed batteries, XI

***

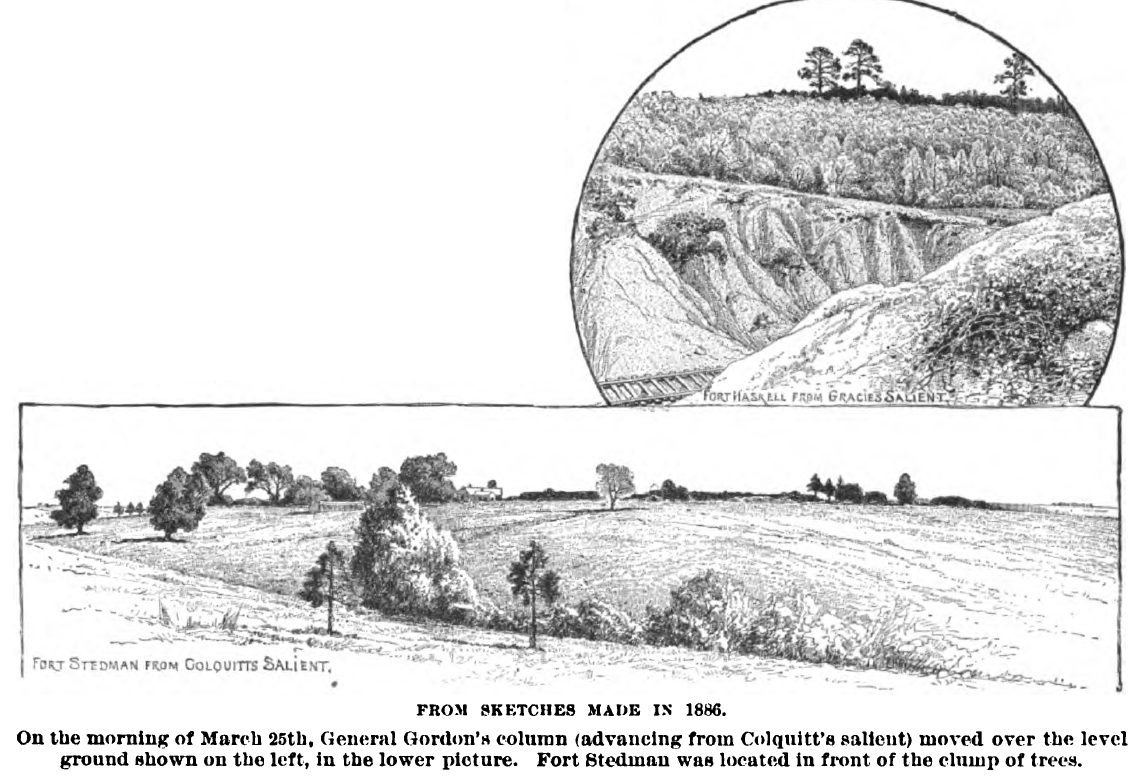

On the morning of March 25th, General Gordon’s column (advancing from Colquitt’s salient) moved over the level ground shown on the left, in the lower picture. Fort Stedman was located in front of the clump of trees.

***

and XII, and the 59th and 29th Massachusetts regiments, stationed near and now under arms.

Meanwhile there was a lull around Haskell; but it was of short duration, for it was now so light that the enemy could observe from his main line every point on the scene of conflict. He opened on Haskell with Stedman’s guns, and also with his own in front. Our little garrison divided, one half guarding the front parapet, the remainder rallying along the right wall to meet the attack threatened by the division coming against it from Stedman. At this juncture, Captain Christian Woerner, of the 3d New Jersey Battery, who had been on duty at the headquarters of the artillery brigade, in the rear, came into the fort and took charge of the

artillery. He placed one piece in the right rear angle, where the embrasure admitted the working of it with an oblique as well as a direct range. About the same time some officers and men of the 100th Pennsylvania and 3d Maryland regiments, who previous to the attack had occupied the breastworks adjoining, came in and were posted on the rear works by Captain George Brennan, of Company

M, who commanded in that quarter. (1) The venturesome Confederate column had borne down all opposition, captured batteries XI and XII, and driven all the infantry from the trenches, and, with closed-up ranks, came bounding along. (2) At a point thirty rods from us the ground was cut by a ravine, and from there it rose in a gentle grade up to the fort. Woerner’s one angle gun and about 50 muskets were all we could summon to repel this column, and there were probably an even 60 cannon and 1000 muskets at Stedman and on the main Confederate line concentrating their fire upon Haskell to cover this charge. (3) The advancing troops reserved their fire. Our thin line mounted the banquettes — the wounded and sick men

***

(1) Lieutenant J. H. Stevenson, of Company K, 100th Pennsylvania, writes under date of December 2d, 1887:

“A little after the alarm was given, all the companies on my right and left were taken to the rear as skirmishers, and I spread my company out in a thin line along our breastworks. Here we stood waiting for the enemy. When the bullets began to come in from the rear I moved my company out for the purpose of being ready to face to the rear. I formed at right angles with the breastworks, but soon found that this was no place for the men and took them into Fort Haskell. My men were posted along the north-east parapet. Only a few could be of service in firing, and the others loaded the muskets.”

J. C. Stevenson, of the same regiment, writes that he was in action in the north-east angle, and was temporarily disabled by the enemy’s fire.—G. L. K.

(2) Among the prisoners taken by this column was our brigade, commander, Colonel McLaughlen (the proper colonel of the 57th Massachusetts). After the repulse of the column on the west front of Fort Haskell, Colonel McLaughlen reached the fort, and, learning the situation, started toward Fort Stedman, attempting to rally the infantry in the trenches on the way. He was captured near Fort Stedman, where he arrived almost alone—G. L. K.

(3) In an artillery duel shortly before this we counted twenty-four mortar bombs in the air at once with pathway directly over the fort.—G. L. K.

***

loading the muskets, while those with sound hands stood to the parapets and blazed away. The foremost assailants recoiled and scattered. The Confederate forts opposite us gave a response more fierce than ever, and a body of sharp-shooters posted within easy range sent us showers of minies. The air was full of shells, and on glancing up one saw, as it were, a flock of blackbirds with blazing tails beating about in a gale. At first the shells did not explode. Their fuses were too long, so they fell intact, and the fires went out. Sometimes they rolled about like foot-balls, or bounded along the parapet and landed in the watery ditch. But when at last the Confederate gunners got the range, their shots became murderous. We held the battalion flag in the center of the right parapet, and a shell aimed there exploded on the mark. A sergeant of the color company was hoisted bodily into the air by the concussion. Strange to say, he was unharmed, but two of his fellow-soldiers, Sergeant Thomas Hunton and Corporal Stanford Bigelow, were killed, and the commandant, Houghton, who stood near the flag, was prostrated with a shattered thigh. This was all the work of one shell. Before our commander could be removed, a second shell wounded him in the head and in the hand.

The charging column was now well up the slope, and Captain Woerner aided our muskets by some well-directed case-shot. Each check on this column by our effective firing was a spur to the Confederates at a distance to increase their fire upon us. They poured in solid and case shot, and had twelve Coehorn mortar-batteries sending up bombs, and of these Fort Haskell received its complement. Lieutenant Julius G. Tuerk, of Woerner’s battery, had an arm torn off by a shell while he was sighting that angle gun. Captain Woerner relieved him, and mounted the gun-carriage, glass in hand, to fix a more destructive range. He then left the piece with a corporal, the highest subordinate fit for duty, with instruction to continue working it on the elevation just set, while he himself went to prepare another gun for closer quarters. The corporal leaped upon the gun-staging and was brained by a bullet before he could fire a shot. The Confederate column was preceded, as usual, by sharp-shooters, and these, using the block-houses of the cantonments along the trenches for shelter, succeeded in getting their bullets into the fort, and also in gaining command of our rear sally-port. All of our outside supports had been driven off, and we were virtually surrounded. The flag-pole had been shot away, and the post colors were down. To make matters still worse, one of our own batteries, a long range siege-work away back on the bluff near the railroad, began to

toss shell into the fort. We were isolated, as all could see ; our flag was from time to time depressed below the ramparts, or if floating was enveloped in smoke; we were reserving our little stock of ammunition for the last emergency, the hand-to-hand struggle that seemed inevitable. The rear batteries interpreted the situation with us as a sign that Haskell had yielded, or was about to yield. (1)

Our leader at Haskell, Captain Houghton, was permanently disabled, but Major Randall had come into the fort soon after Houghton fell. With the men of the Stedman battalion who had reached us, he now joined in the defense. When the fire from our rear batteries became serious, Major Randall called for a volunteer guard to sally with the colors, in rear of the fort, to show the troops behind us that Haskell was still holding on. Our colorbearer, Robert Kiley, and eight men responded. Randall led the way along the narrow bridge-stringers over the moat (the planks having been removed to prevent a sudden rush of the enemy) and the flag was waved several times in the faces of the Confederates, who hung about the rear of the fort, and who opened fire upon the colors. Four of the guard were hit, one being mortally wounded, but the fire from our rear batteries ceased.

The ranks of the enemy soon broke under the fire of our muskets and Woerner’s well-aimed guns, but some of the boldest came within speaking distance and hailed us to surrender. The main body hung back beyond canister range near the ravine at the base of the slope, but within range of our bullets. Captain Woerner at last held his fire, having three pieces on the north front loaded with grape. Suddenly a great number of little parties or squads, of three to six men each, rose with a yell from their hidings down along those connecting parapets, and dashed toward us. The parapets joined on to the fort, and upon these the Confederates leaped, intending thus to scale our walls. But Woerner had anticipated this; the rear angle embrasure had been contrived for the emergency, and he let go his grape. Some of the squads were cut down, others ran off to cover, and not a few passed on beyond our right wall to the rear of the work and out of reach of the guns. With this the aggressive spirit of that famous movement melted away forever.

To Gordon, the dashing leader of the sortie, it was now no longer a question of forging ahead, but of getting back out of the net into which he had plunged in the darkness. The way of retreat was back over the ridge in front of Stedman. This was swept by two withering fires, for Fort Haskell commanded the southern slope of the ridge, and Battery IX (2) and Fort McGilvery the northern. With

***

(1) A message to this effect was taken to one of the distant siege batteries, with the request to fire upon us. The commandant refused.—G. L. K.

(2) George M. Buck, 20th Michigan Volunteers, sends us the following concerning the action on the light of Fort Stedman:

“Between Forts Stedman and McGilvery [see map. p. 538] there was an earth-work known to the troops investing Petersburg as Battery IX. It was occupied during the closing weeks of the siege by the 20th Michigan Infantry, two guns of Batteries C and I, 5th United States Artillery, and three Coehorn mortars served by Company K, 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, with the 2d Michigan Infantry in the rifle-pits immediately to the left. Both of these regiments belonged to the Second Brigade, of Willcox’s division, commanded by Colonel Ralph Ely. Between Battery IX and Fort McGilvery ran the City Point and Petersburg road. On the morning of March 25th, before daybreak, the soldiers of the 2d and 20th Michigan learned that Fort Stedman was in the hands of the enemy, and the former retired within Battery IX, and with the 20th Michigan and the two guns of the [SOPO Editor’s Note: Continued in notes section at the bottom of the next page.]

***

either slope uncovered the retreat would be comparatively easy and safe for Gordon, and the Haskell battery was the one at once able to effect the severest injury to his retreating ranks, and apparently the easiest to silence. The rifle and mortar batteries and sharp-shooters in our front took for a target the right forward angle of Haskell, the only point from which Woerner’s guns could reach that coveted slope. A heavy fire was poured into this angle, while the Confederates in Stedman began to scramble back to their own lines. Woerner removed his ammunition to the magazine, out of reach of the bombs that were dropping all about the gun. His men cut fuses below and brought up the shell as needed. The brave soldier mounted the breastworks with his field-glass and signaled to the gunner for every discharge, and he made the slope between Stedman and the Confederate salient (Colquitt’s) a place of fearful slaughter. My mind sickens at the memory of it — a real tragedy in war—for the victims had ceased fighting, and were now struggling between imprisonment on the one hand, and death or home on the other. Suddenly an officer on a white horse rode out under the range of Woerner’s gun and attempted to rally the panic-stricken mass. He soon wheeled about, followed by some three hundred men whom he drew back out of range, halted, and formed for a charge to silence the gun. The movement was distinctly observed by us in Haskell, and Woerner continued to pound away at the slope, while the infantry once more formed on the parapets. The

storming-party moved direct on our center, as if determined now to avoid contact with the guns of either angle. But our muskets were well aimed, and the new ranks were thinned out with every volley. The party crossed the ravine, and there the leader fell, shot through the head. Many of his men fell near him, and the last spasm of the assault was ended. Gradually the fire on both sides slackened, and many of the Confederates that were still within our lines laid down their arms.

Major Randall now resolved to recapture Fort Stedman, and taking a number of the men of the 14th Regiment, belonging to the Stedman battalion, formed on the parade in rear of Haskell. He was soon joined by detachments of officers and men from the 3d Maryland, 100th Pennsylvania, and 29th Massachusetts regiments, and the column charged down the breastworks to Fort Stedman, the 3d Maryland men, led by Captain Joseph F. Carter, being the first to enter the work and demand its surrender. At the same time Major N. J. Maxwell, of the 100th Pennsylvania, and a number of his men, mounted the parapet and planted their colors there. This column re-occupied Fort Stedman and Battery X and the breastworks, and the prisoners and rifles captured were awarded to the officers of McLaughlen’s brigade, who led the counter-charge from Fort Haskell. Randall and his men took possession of the recaptured works and continued to garrison them. (1) [See, also, General Hartranft’s article, p. 584 and following.]

***

[SOPO Editor’s Note: Continued from notes section of previous page.] battery repulsed no less than three vigorous and determined assaults of the enemy. In repelling these assaults Fort McGilvery rendered efficient assistance. Captain Jacob Roemer, commanding the artillery there, finding at one time that he could not incline his guns sufficiently to reach the assaulting column, had two pieces hauled out of the fort and planted them near the City Point road. Battery IX endured for several hours the incessant and concentrated fire of the “Chesterfield” and “Gooseneck” batteries, the mortar-batteries in front, and the guns of Spring Hill on the left, besides the desperate and stubborn attacks of infantry greatly superior in numbers to those within the battery. And while the attempt to capture Battery IX was probably not so furious or sanguinary as that upon Fort Haskell, it was sufficient to test to the highest degree the courage and endurance of the men. In his official report of the battle, General Willcox, the division commander, says: ‘The 2d Michigan fought the enemy on this flank … in the most spirited manner, until they were drawn in by order of their brigade commander (Colonel Ralph Ely) to Battery No. IX.’ And when ordered into Battery IX, the movement was executed in order, with steadiness and without confusion, though the regiment was heavily pressed by the skirmishers of the enemy, in both flank and rear. On the morning of the 25th, after the final assault and repulse, a Confederate captain, who was one of the prisoners taken from the enemy, told me that the column making the lust assault on Battery IX was composed of two brigades, Ransom’s and another, the name of the commander of which I have forgotten. He stated that the orders to the attacking party were to move upon the flank and rear of our line, clear the works to McGilvery, and take the fort by assault in the rear. As he expressed it, the assailants got along well enough till they ‘came to this rise (indicating Battery IX), where you-uns sort of discouraged us.’ Mention should be made of the service performed by the other regiments in our brigade, and also by Fort McGilvery, Battery V, and Battery IV, the two latter being batteries firing at long range.” EDITORS.

(1) The loss in the four companies of the 14th New York, in Fort Haskell, was 4 killed and 23 wounded. The 3d New Jersey Battery lost 1 killed and 7 wounded. The eight companies of the 14th New York stationed at Fort Stedman lost 8 killed, 22 wounded, and 201 captured or missing. The two sections of the 19th New York Battery, in Fort Stedman, lost 1 killed and 14 missing. The section of the 14th Massachusetts Buttery, in Battery X, lost 1 killed (Lieut. Nye), 2 wounded, and 11 missing. The loss of the Ninth Corps in repulsing the attack on Stedman, Haskell, etc., was 70 killed, 424 wounded, and 523 captured,—In all, 1017.—EDITORS.

***

Source: