ACTIONS ON THE WELDON RAILROAD.1

BY ORLANDO B. WILLCOX, BREVET MAJOR-GENERAL, U. 8. A.

I. GLOBE TAVERN.

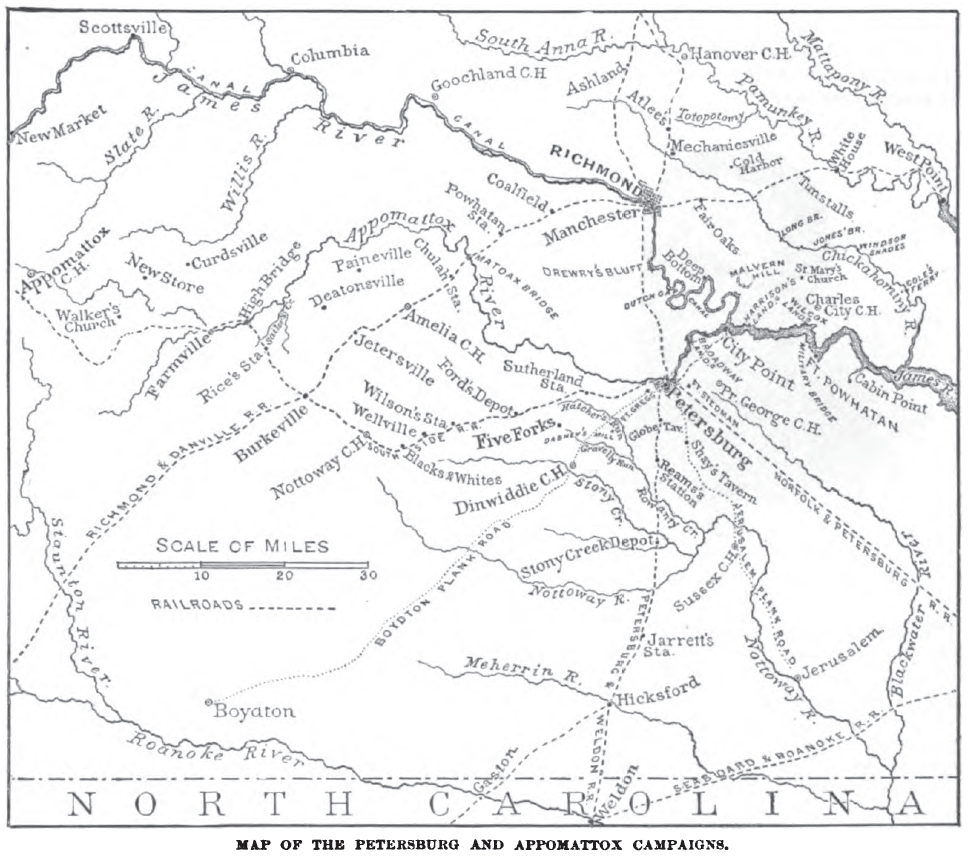

The operations on the railroad connecting Petersburg with Weldon, North Carolina, were a bit of strategy conceived by Grant in connection with Hancock’s and Butler’s movements north of the James, in order to force a withdrawal of the enemy’s troops operating against Sheridan in the valley, and were intended by Meade to cut off one more avenue of supplies to Petersburg. Meade also wanted to attack the intrenchments on the south side of the James, believing that Hancock’s move had drawn off all but two divisions from the defenses; but in this ho was overruled by Grant.

The movement therefore became a reconnoissance in force, with instructions to the commander, General G. K. Warren, to make the best of any advantages that might be developed, to effect a lodgment on the railroad as near the enemy’s fortifications as practicable, and to destroy the road as far down as possible. The track had already been pretty badly cut up by our cavalry, but only in spots and not beyond speedy repair. Warren started out early on the morning of August 18th, 1864, with his own (Fifth) corps, and a brigade of General A. V. Kautz’s division of cavalry, under Colonel Samuel P. Spear. The heat was intense and the country so drenched with rain that the fields were well-nigh impassable for artillery. Griffin took the lead, with his division and Spear’s cavalry, met the enemy’s pickets a mile from the road,— which was guarded by General James Dearing’s brigade of cavalry,— deployed his skirmish-line, and advanced rapidly on the road in column of brigades, then turned to the south and west. Ayres followed, but wheeled toward the city, with Crawford’s division in column on his right and Cutler’s division in reserve.

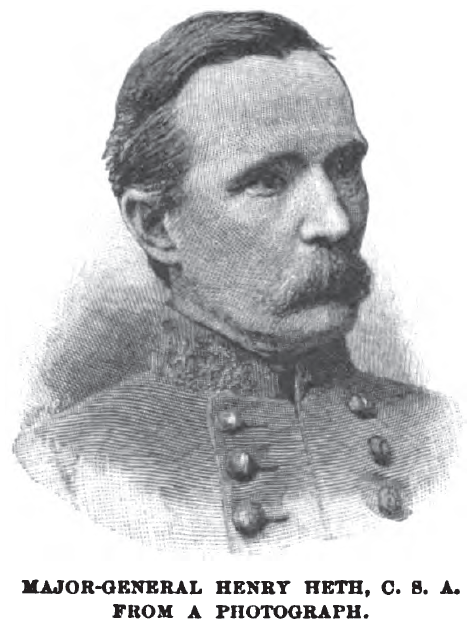

A report by Dearing to General Beauregard, commanding the defenses of Petersburg, enabled that commander to get troops on the road, and after a mile’s march Ayres found himself confronted by General Heth’s division of Hill’s corps, in position, with artillery. At the first encounter Ayres was forced to fall back a little to prevent the turning of his left flank, but he quickly rallied and finally, by the help of Hofmann’s brigade of Cutler’s division, drove Heth from the ground, though with very heavy loss. To what extent this advantage might have been immediately followed up is a disputed question. Crawford’s left was somewhat engaged, but his passage through the thick woods and swampy ground, cut up with ravines, was found difficult. He could not keep up with Ayres, and Warren halted within a mile or two from the Vaughn road intersection.

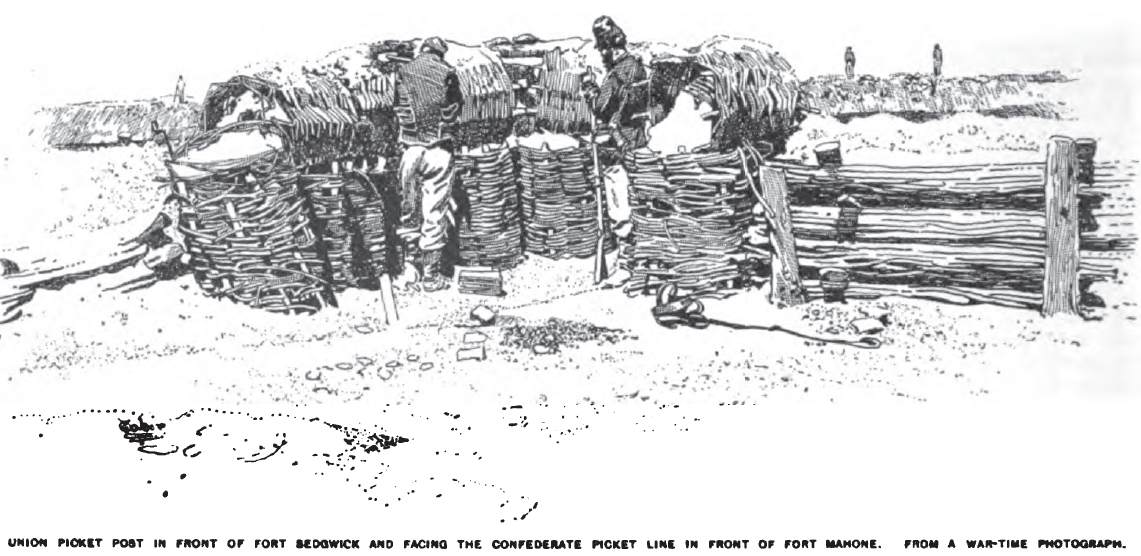

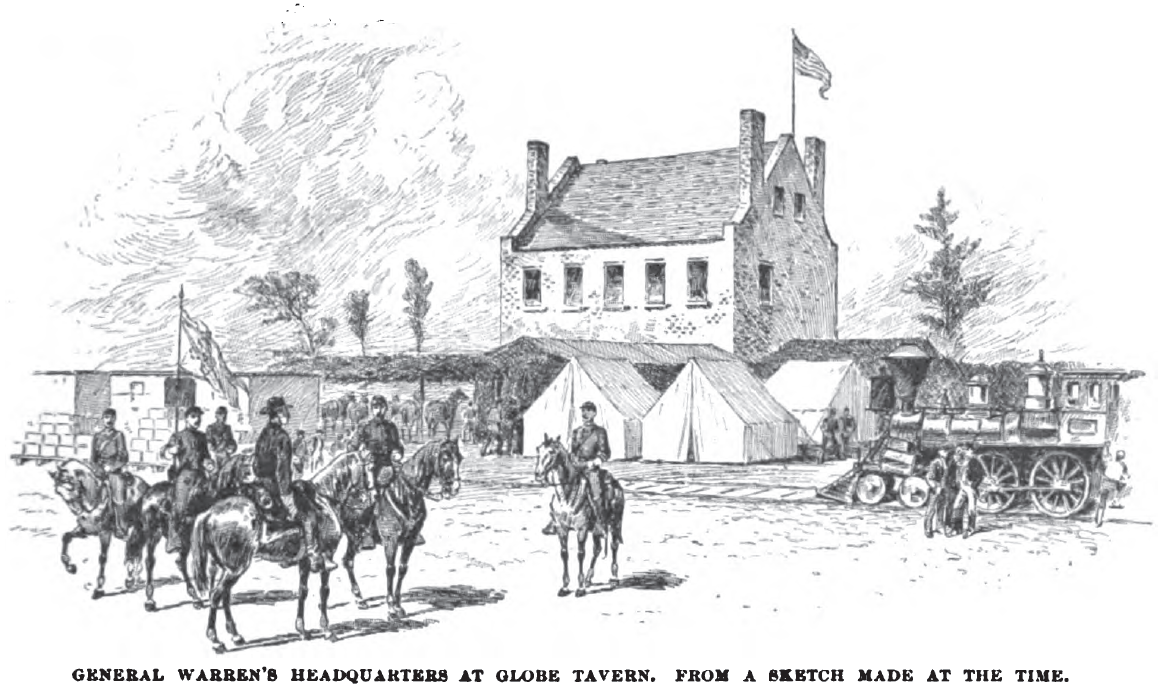

The intersection was the point Meade most wanted Warren to gain. However, he was pleased sufficiently as it was, and ordered Warren to maintain his hold on the road “at all hazards.” He directed Mott’s division, Second Corps, to establish a connection with the new works, and ordered out Willcox’s, White’s(1), and afterward Potter’s divisions from the Ninth Corps’ works to reenforce Warren; these to be followed finally by Gregg’s cavalry brigade and two hundred railroad men to destroy the tracks toward Reams’s Station. My division being nearest was first to arrive next morning, and was ordered to bivouac near the “Globe Tavern,” where Warren had his headquarters. When White came up he was posted farther to the right.

Beauregard likewise ordered out reinforcements, under Lieutenant-General A. P. Hill, viz., three brigades under Mahone, Pegram’s batteries, and W. H. F. Lee’s cavalry — all of whom, with Heth’s brigades, were concentrated at the Vaughn road

***

(1) General Julius White had commanded a division in the Twenty-third Corps, in Burnside’s army in east Tennessee. Immediately after the mine explosion, July 30th, he relieved General James H. Ledlie in command of the First Division, Ninth Corps.— Editors.

***

junction for an attack during the afternoon of the 19th.

Heth opened on Ayres’s front, while Mahone, who was best acquainted with the woods, burst in Ayres’s right and swept down on Crawford in column of fours, carrying off Crawford’s skirmishers, and seizing parts of the main line, and compelling Ayres’s right and Crawford’s line to fall back. For a short time chaos and confusion reigned, Crawford fighting on all sides, and pieces of artillery of both armies pouring their fire into the intermingled mass of friend and foe — ranks there were none. Crawford himself was at one moment a prisoner and escaped “by miracle,” while of the other prisoners captured, some were secured and others fled or were rescued. In this melee Captain Newbury was shot by a rebel officer to prevent his rescue, and died in the arms of his own men with the avowal on his lips. The confusion was scarcely over before our Ninth Corps got up.

Hearing the attack on Ayres my division was first ordered in his direction, toward the left. But as the firing quickly became general along the line and men came streaming out everywhere. I ordered my First Brigade, General John F. Hartranft, forward into the woods, and Colonel William Humphrey with the Second Brigade to support him in the direction of Crawford’s right front.

Hartranft encountered a line of troops, probably Clingman’s brigade, coming through a strip of timber. They had penetrated some six hundred yards in the right and rear of Crawford’s works, and through a corn-field, giving them full view of the space around Globe Tavern and all our movements. Hartranft threw forward his right regiments, and advancing thus drove the fellows back through the edge of the woods and into the field, capturing a good lot of prisoners. The enemy, collecting in the corn-field again, came forward, while Hartranft brought up his left wing, and now drove them ”under a terrific fire of musketry” across that field into the farther woods; there they once more rallied and came out, this time to within seventy-five yards of us, but were again driven to cover just as Humphrey’s brigade closed up.

About this time I received orders from Warren to send a brigade to the left of Crawford and right of Ayres, and Humphrey was started over. Humphrey fell foul of the enemy, one of Mahone’s brigades, coming through the trees. Both sides halted and commenced firing, but the Confederates soon fell back to the captured works. Moving a little further to the left, Humphrey formed his men in two lines and made a charge, in which he succeeded in driving the enemy from the works at the point designated by Warren, capturing a

battle-flag and quite a number of prisoners. In this charge fell Major Horatio Belcher, of the 8th Michigan, while waving on his “Wolverines” with his wonted enthusiasm.

The achievement of these works,— more strictly, rifle-pits,— says Colonel Humphrey, a most truthful and unassuming man, was effected without connection with other troops, on either flank, where the works were recaptured later, as will be seen further on, when Ayres on his left and Crawford on the right came up with their troops(1).

Meanwhile, the battle began to rage again on our right. Scarcely had Hartranft started over to support and connect with Humphrey, leaving the ground that he had gained to be occupied by White, When White was attacked by Colquitt. Warren ordered me to assume command of both divisions and I ordered Hartranft to support White. His support was scarcely needed, for, refusing his right wing, as he had been previously directed by Warren, to prevent another such disaster as had opened the proceedings, White repulsed the attack completely. Beauregard telegraphed Lee, with reference to the attacks on Hartranft and White, that “Colquitt and Clingman, in advancing through the thick undergrowth, lost their organizations, and were ordered to their camps to rally them.”

Meantime, Edward S. Bragg’s brigade of Cutler’s division had been ordered up to support and help reestablish Ayres’s broken right, which it gallantly did, encountering a small force on its way; Crawford also had somewhat re-formed his broken battalions. These preparations being made, Warren ordered us all to attack and recapture the lost rifle-pits yet remaining in the enemy’s hands, and about the time that White was driving Colquitt the general advance was handsomely made. Not only were our rifle-pits everywhere retaken, but rows of

muskets in stacks — perhaps those left by our own men — were captured as they stood. Heth alone held his grip in front of Ayres, and remained unbroken. He had made two assaults during the day, both without shaking Ayres, and at a loss of some prisoners as well as a flag. Just before dark — a favorite hour for the enemy’s assaults — the stubborn Heth made his third, last, and most desperate attack. But Ayres was stronger, both in troops and position. His volunteers emulated his regulars in their enthusiastic bravery, and such isolated assaults on intrenched lines hardly ever prove successful. Besides the reenforcements mentioned Griffin had sent over a brigade to strengthen his classmate(2). And it was now classmate against classmate. With the odds so much on one side the result might have been, and probably was, anticipated; but “war is a game of chances.” Heth was ignorant of the reenforcements and calculated on Ayres’s weakness from his shifting back his right. He made a most gallant charge, was repulsed, and, strange to say, was suffered to retire without a counter-charge.

Down on the left and rear General W. H. F. Lee had made strenuous attempts to turn our flank, but Spear, supported by Griffin at the end of the line, not only stood him off there, but reported at night that he had driven Lee to within a mile of Reams’s Station. There was much jubilation in our camps that night. Warren felt happy and was lavish in praise of all, generously thanking me and the Ninth Corps troops present for what he was kind enough to say had “saved the day.” General Meade telegraphed that “he was delighted to hear the good

***

(1) This incident is overlooked by Warren in his report, which I find in the “War Records” Publication Office, and which was written before he received copy of my own report through Ninth Corps headquarters.— O. B. W.

(2) Ayres, Griffin, and myself were members of the same graduating class at the Military Academy, West Point, and so were two of our opponents on this field, A.P. Hill and Heth.— O. B. W.

***

news, and congratulated Warren and his brave officers and men on their success,” adding, “it will serve greatly to inspirit the whole army, and proves that we only want a fair chance to defeat the enemy. I hope he will try it again.” Well did that army need cheering up, for it had been under a black cloud ever since the fatal mine affair, and felt the long strain of the trenches on its nerves. On the 20th Warren drew back his line about a mile to more open ground, where his artillery might play its part; and on the 21st Hill reappeared before him to “try it again” with his own corps and W. H. F. Lee’s cavalry, reenforced by part of Hoke’s division of Ewell’s corps. Hill was a dashing general, and he made a gallant effort on Warren’s lines, now pretty well intrenched, assaulting under cover of a cannonade of thirty guns. But Griffin and Ayres were both old artillerists, and Hill’s long, serried lines were smashed by our guns before they got within reach of our musketry. Later in the day Mahone selected a point, and “hurled” his division with his well-known fiery energy fairly up to our works on the left, but in vain. Hagood’s brigade alone got inside, and were there made prisoners in a body, though part of them, in the confusion and delay to take them in, re-opened fire and made their escape. Besides all the wounded, over two hundred Confederates lay dead upon the field in front of our defenses — a sad sight, for, enemies as they were, they were bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh. Thus ended the last and most reckless attempt to dislodge Warren.(1)

II. REAMS’S STATION.

Ever since the first investment of Petersburg both sides had appreciated the importance of the Weldon Railroad, and every attempt on our part was fiercely contested by the rebels. Wilson’s cavalry raid was started off against that and the Lynchburg Railroad on June 22d by General Meade. [See p. 535.] Late in August, in view of the success of the Fifth and Ninth corps at Globe Tavern, it was determined to continue the work of destruction down on this much-fought-for railway. For this purpose Hancock was ordered over from Deep Bottom with two divisions to Reams’s Station. He arrived there on the 22d, after a most fatiguing march, and set to work at once with his accustomed promptitude and energy, and without rest. He found the station house burnt, and some sorry intrenchments in a flat, woody country, where two roads crossed, which had been hastily thrown up during the June operations, but which he did not stop to improve: one from the Jerusalem plank-road, by which he had marched; the other from the Vaughn road, running from Petersburg to Dinwiddie Court House. He found the roads picketed by Spear’s brigade of cavalry, and to this he added D. McM. Gregg’s cavalry, which he had brought along.

Hancock had torn up and burned some miles of the track, when, on the evening of August 24th, Meade notified him that bodies of troops, estimated at ten thousand, were seen by the signal men moving within the Confederate lines to our left, and advancing down the Halifax-Vaughn road. It might be intended to attack either Warren’s left, or Reams’s Station. Meade thought the latter the more likely.

For some time next morning nothing appeared before Hancock but the usual parties of W. H. F. Lee’s cavalry, that had sought to interrupt the

***

(1) The total Union loss was 351 killed, 1148 wounded, and 3879 captured or missing = 4278. The Confederate loss is not officially stated.—Editors.

***

work of our men, but were easily kept off by Gregg, who held the roads toward Dinwiddie Court House and Petersburg. Gibbon’s division was about to proceed down the track to resume its labors when Spear, farther down to the left, reported the enemy advancing in force. Gregg deployed and advanced to meet them, and developed the fact that their cavalry was supported by infantry. During the skirmish a party broke through Gregg’s pickets to the left and rear. This party was driven back by a regiment of our cavalry with its infantry supports, and the whole  demonstration — probably a reconnoissance — was over. Prisoners taken in the skirmish proved to be from C. M. Wilcox’s, Heth’s, and Field’s divisions, of A. P. Hill’s command. In fact, there were nine brigades, including two of Mahone’s, and Pegram’s artillery, present or coming up. Developments so far were reported to army headquarters and preparations were made for a vigorous defense. Gibbon’s division was drawn into the left breastworks, which were strengthened and extended somewhat to the rear, and Miles, with Barlow’s division, occupied the right. Both flanks were exposed to reverse fire from the front, as may be easily seen from Hancock’s map. Until 12 o’clock all communications with Meade were by couriers through Warren’s headquarters. At noon the field telegraph line was brought down to within half a mile. It was not until 2 o’clock that the enemy made another move, when they attacked Miles,

demonstration — probably a reconnoissance — was over. Prisoners taken in the skirmish proved to be from C. M. Wilcox’s, Heth’s, and Field’s divisions, of A. P. Hill’s command. In fact, there were nine brigades, including two of Mahone’s, and Pegram’s artillery, present or coming up. Developments so far were reported to army headquarters and preparations were made for a vigorous defense. Gibbon’s division was drawn into the left breastworks, which were strengthened and extended somewhat to the rear, and Miles, with Barlow’s division, occupied the right. Both flanks were exposed to reverse fire from the front, as may be easily seen from Hancock’s map. Until 12 o’clock all communications with Meade were by couriers through Warren’s headquarters. At noon the field telegraph line was brought down to within half a mile. It was not until 2 o’clock that the enemy made another move, when they attacked Miles,

were repulsed, and again attacked more vigorously, and were again repulsed, this time leaving their killed and wounded within a few yards of Miles’s front.

Meantime Meade had ordered all the available troops from Mott’s division that were on Warren’s right to move down the plank-road to its intersection with the Reams’s Station cross-road, four miles back from the station, and report from there to Hancock. And now, since this last attack at 2: 45 p. M., Willcox’s division of the Ninth Corps, held in reserve on Warren’s center, was ordered to the same point. Hancock had been advised by telegraph from Warren’s headquarters, where Meade had come to be in closer communication: “Call him [Willcox] up if necessary”; and the dispatch adds: “I hope you’ll give the enemy a good thrashing. All I apprehend is his being able to interpose between you and Warren.”

I proposed to the officer who brought me my orders — I forget whether it was General Parke, commanding the Ninth Corps(1), or a staff-officer— to march straight down the railroad, four or five miles at most, and join Hancock at once, instead of marching round twelve miles by the plank-road, but was told that there was some apprehension of the enemy’s getting round Hancock’s left and rear, and that I must look out for that side. We passed the Gurley House at 3:55, marched across lots to the plank-road, and down to the cross-roads at Shay’s Tavern, where we arrived before 6, and received a message from Hancock calling me up rapidly. My troops were in good spirits. They heard the cannon-firing and felt that, having assisted Warren of late materially and in the nick of an extremity, they were rather honored by this call from the grand old Second Corps, and we pushed ahead at a swinging gait. Very soon we began to meet stragglers from the front, and some wagons and ambulances. Farther on an orderly handed me an order(2) from Hancock to arrest the stragglers and “form them according to their regiments,” for which I had to deploy and leave the 20th Michigan Infantry, and that delayed us a little of course. With the rest of the division I pushed on, without halting, until 7 o’clock, when I received word that if one or two brigades could be got up in time the day might yet be saved. This was communicated to the troops, who threw off their blanket rolls and started at a double-quick, which they kept up, with few breathing intervals, the rest of the way until I reported to Hancock.

Meantime a bitter fight had been going on. After the 2 o’clock affair everything looked promising to Hancock for an hour or two. However, the rest of Hill’s troops were coming up, and the chopping of trees and the rumble of artillery were heard in the forest. Hancock only felt solicitous to keep the road open leading to the plank-road, up which he looked for aid, “if necessary,” and by which he must retreat if worsted. At 4:15 he became more anxious, and telegraphed Meade

***

(1) On August 18th General Burnside was granted a leave of absence and General John G. Parke was assigned to the command of the Ninth Corps. General Burnside resigned April 15th, 1865.—Editors.

(2) This order was intended for the officer commanding Mott’s troops, still at Shay’s Tavern.— O. B. W.

***

that heavy skirmishing was going on, and an attack pending, probably, on the left. He desired, as he said to Meade, ”to know as soon as possible whether you wish me to retire from this station in ease we can get through safe — think it too late for Willcox; had he come down the railroad he would have been in time. Have ordered up Mott’s division by way of precaution.” Evidently he expected Mott first at the junction.

At 5 o’clock Hill had opened with his artillery, both shot and shell, some of which took the works, so-called, in reverse, but did little actual damage other than demoralizing the men, of whom there were many, even in the old regiments, who never had come to fight, but to run on the first chance, or get into the hospital, and, ho! for a pension afterward! “Some of their officers could not speak a word of English,” says Hancock in his report, and were therefore without that mutual intelligence and support which battle demands, and with nothing in common with their men but panic.

The first assault came on Miles, opposite his Fourth Brigade, and at a part of the line held by the consolidation of material of different regiments. For a time the severity of Miles’s fire, the slashing and other obstacles on the ground, staggered the assaulting column, and they must have baffled it completely if the fire had continued only a few minutes longer. As it was, the assailants were thrown into considerable confusion when, suddenly, our recruits gave way, and a break occurred of two regiments on the right, and though Miles ordered up what little reserve he had these men would neither move forward nor fire. Still Lieutenant George K. Dauchy, of McKnight’s 12th New York Battery, turned his guns on the breach with effect, until the enemy crept along the silent rifle-pits, captured the battery, and turned a gun inside our lines. Murphy’s brigade of the Second Division being likewise driven off, the enemy captured the 10th Massachusetts Battery, and Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Artillery, on his front, though it was served with “marked gallantry” to the last.

Gibbon’s division was ordered to retake the works that were thus lost, but the men responded feebly, and fell back to their other works. Here, however, they were exposed to such an interior fire that they were compelled to throw themselves over to the outside of their parapet. Affairs looked desperate. But the gallant and indefatigable Miles, rallying some brave men of the 61st New York, formed line at right angles, swept down, recaptured considerable of the ground lost, including McKnight’s battery, and threw two hundred men across the railroad, threatening the enemy’s rear. This force was insufficient to hold their advantage, and Gibbon’s fellows were ordered to reenforce it. But in vain. “They could not be got to go up,” said the veteran, who, with his staff, tried his best, with sword and expostulations. His own side was soon attacked “by dismounted cavalry, and driven from their breastworks with little or no resistance,” until some dismounted regiments of Gregg’s and Spear’s cavalry, fighting with bravery that shamed our infantry, rescued the prize from the enemy, who finally fell back. Gibbon partially rallied his men behind the right wing, and formed a new line of pits a short distance to his rear, on the left of which Gregg withdrew his troopers.

Every attempt subsequently made by the enemy was successfully repelled(1).In one assault Miles made a counter-charge and recaptured part of his lost line and a gun, and so matters stood at my arrival near the scene of action some time before dark. With the assistance of my division it did not seem too late to recover everything that had been lost. But, considering the utter demoralization of one of his divisions, and the fatigue of all the brave men that had stood, Hancock did not think it wise to renew the fight that evening, though both Miles and Gregg offered to retake their portions of the works. Nor did he think it worth while to sacrifice any more men for an object that was so far accomplished that, previous to the action, he had telegraphed Meade his own intention to withdraw that night anyhow. Nothing more could be done to destroy the railroad now, and consequently there was nothing to keep Hancock at the station. “Had our troops behaved as they used to I could have beaten Hill,” he said to me. “But some were new, and all were worn out with labor. Or had your force been sent down the railroad to attack the enemy’s flank we would have whipped him; or a small reserve about 0 o’clock would have accomplished the same object.” These points were also mentioned in his report(2). He requested me to draw up my division as a rearguard and let his troops pass by after dark. I never had seen him in better form. It was more like abdication than defeat.

The enemy did not attempt to follow us(3).

***

(1)Captain Christian Woerner’s 3d New Jersey Battery rendered important service at this time.— Editors.

(2) General Humphreys in a letter to me of October 9th, 1883, says:

“I considered your not having taken part in the fight to be due entirely to the route you were ordered to take, as indeed it was. Meade was at Warren’s headquarters. I was at headquarters Army of the Potomac. The telegrams were all taken off for me and I was sorely tempted to telegraph Meade to send you down the railroad to hit the enemy in flank, but refrained from delicacy, to my great regret ever since.”

The general also furnished me with copies of notes intended to correct mistakes and fill omissions which occurred in his history,”The Virginia Campaign of 1864 and 1865,” and which are corrected and supplied in these articles, so far as the Weldon Railroad fights and my division are concerned.— O. B. W.

(3)The Union loss was 140 killed. 529 wounded, and 2073 captured or missing=2742. The loss of the Confederates reached a total of 720, mostly in killed and wounded.—Editors.

***

Source:

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 4, pages 568-573 ↩