March 31, 1865: Lee Punishes a Probing Fifth Corps…But Is Forced to Fall Back

The Battle of White Oak Road was fought on March 31, 1865, 150 years ago today, along with the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House. This day’s actions were the twin penultimate battles of the Five Forks “mini-campaign,” and caused the fateful joining of Phil Sheridan’s cavalry force with Gouverneur Warren’s Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac. March 31 would also feature Robert E. Lee directing events on the White Oak Road on the Confederate side.

In my post yesterday, I discussed the situation on March 30, including the all-day rain, which prevented any heavy fighting that day. That was not going to be the case the next day. A circular containing directions for the Fifth Corps’ division commanders was sent at 11 p. m. on the night of March 30:

“General Ayres will re-enforce his advance at daylight tomorrow morning with his whole division. General Crawford will hold his command ready to follow General Ayres. General Griffin, as soon as relieved by General Humphreys’ troops, will move down the Boydton plank road to where General Ayres now is.”

As the rain ended on the morning of March 31, General Warren knew he could get onto the White Oak Road west of the Confederate lines held by Bushrod Johnson. This all-important point would allow Warren to position himself between Johnson’s line and Pickett’s force at Five Forks. He sent a message to George Meade at 9:40 a.m. that he was moving Ayres’ Division in that direction:

“I have just received report from General Ayres that the enemy have their pickets still this side of the White Oak road so that their communication is continuous along it. I have sent out word to him to try and drive them off or develop with what force the road is held by them.”

George Meade only received this dispatch at 10:30 a. m., and shot off the following reply immediately:

“Your dispatch giving Ayres’ position is received. General Meade directs that should you determine by your reconnaissance that you can get possession of and hold the White Oak road you are to do so notwithstanding the orders to suspend operations to-day.”

Before Warren ever received this reply, he had moved Ayres forward in the direction of the White Oak Road. This movement in the direction of such a sensitive spot goaded the Confederates, just like someone poking a stick at a hornet nest, setting off a wild back and forth fight that saw two Fifth Corps divisions flee in confusion and disorder.

In yesterday’s post, I mentioned a Confederate council of war at Sutherland Station. It guided Confederate efforts on March 31. While George Pickett’s mixed infantry/cavalry force attacked Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House in an effort to protect Five Forks, no less a personage than Robert E. Lee himself would oversee a division-sized attack at the White Oak Road. Lee, who was directing operations in the area today due to the consequences of any failure, would launch the attack in an effort to protect the White Oak Road leading west to Five Forks. If the Union troops were able to reach this point in strength and cut off Pickett from a direct connection with the remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia, Petersburg and Richmond’s days were numbered.

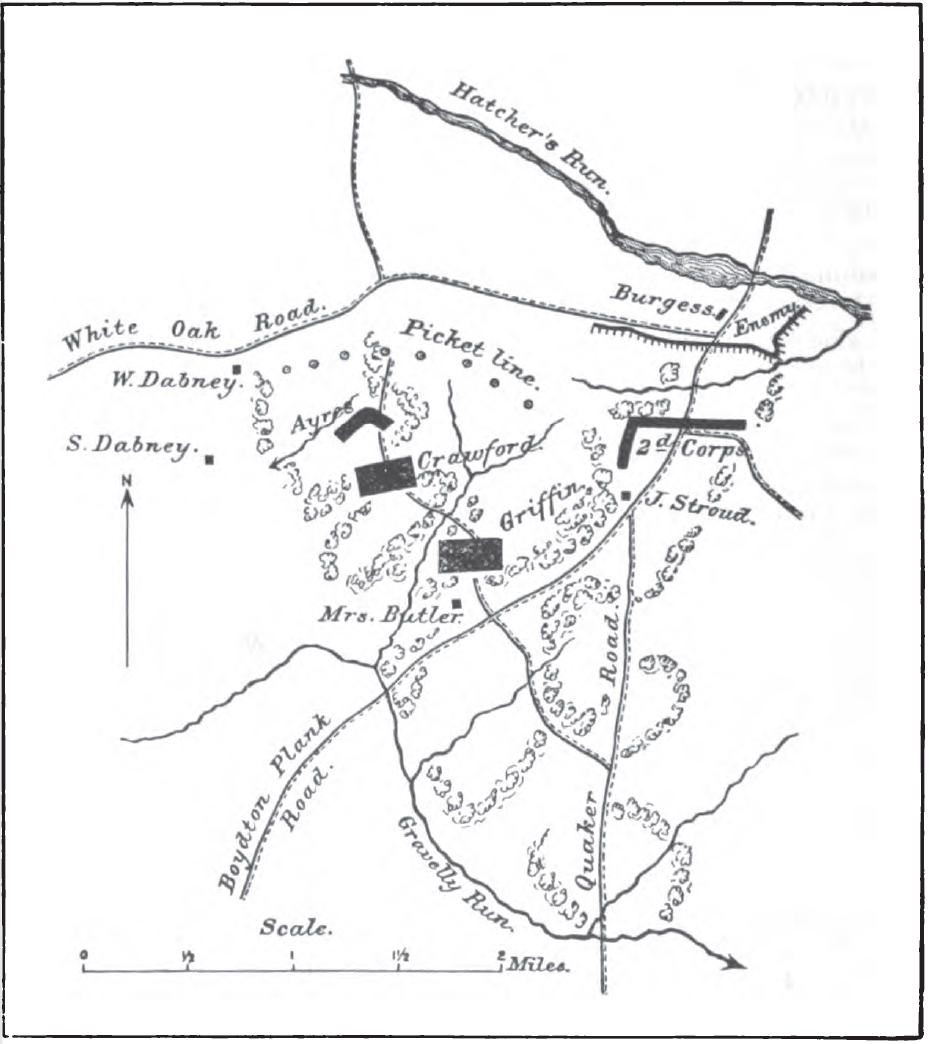

Fifth Corps Position Prior to Ayres’ Advance: 10:30 AM March 31, 1865

As things stood at 10:30 a. m. on March 31, 1865, Ayres’ Fifth Corps division jutted out like an inquisitive finger, probing for the exposed and vulnerable Confederate communications along White Oak Road west of their intrenchments. Warren made a tactical blunder by sending Ayres ahead on his own, followed by Crawford’s Division in another line behind. Griffin, recently relieved by Miles’ Second Corps division to the east the night before, had moved down to the area just behind a small tributary of Gravelly Run. His position proved to be fortuitous. Fred Winthrop’s Brigade of Ayres’ Division moved forward just before 11 a. m. in an effort to entrench on the White Oak Road and cut Confederate communications. He was within yards of the road when the Confederate attack hit at 11.

Robert E. Lee spent the morning watching the Union troops coming on, and when Winthrop’s Brigade made its fateful push north the Confederates were ready. Bushrod Johnson informed Lee that Ayres’ Division had its left flank carelessly in the air and Lee determined to take advantage. The problem was that the Confederates didn’t have a strong or cohesive force with which to attack. McGowan’s South Carolinians of Wilcox’s Division, Hunton’s Virginians of Pickett’s Division, along with Moody’s Alabamians and Wise’s Virginians from Johnson’s own division made up the available men. They weren’t used to serving with each other, but they were the units present and Lee had to make do with what he had. They would go into the fight under the immediate tactical supervision of division commander Bushrod Johnson.

As Ayres’ men neared White Oak Road, the Confederates weren’t entirely yet in position to attack. Hunton’s Virginians, unable to restrain themselves, prematurely attacked Winthrop. The men of McGowan and Moody (the latter brigade led by Col. Stansel today) followed. This rather small assault paid outsized dividends, much like many of William Mahone’s earlier assaults during the Siege. Not only Ayres’s Division but also Crawford’s were driven back in a panic all the way over the branch of Gravelly Run where Griffin’s Division was posted. In his official report, division commander Ayres naturally understated the disaster:

“The morning of the 31st I was ordered to move my division in that direction. I took up a position in a field lying east of Dabney’s and extending to the White Oak road, posting the Second Brigade on the left and facing the Dabney place. Soon after I received from the corps commander an order, through Major E. B. Cope, aide-de-camp, to take the White Oak road and intrench a brigade upon it. I was furnished one brigade of the Third Division as support, which I posted across the field in the position occupied by the First Brigade before it moved forward. I ordered forward the First Brigade, supported on the right by the Third. As the troops arrived within about fifty yards of the White Oak road the enemy’s lines of battle rose up in the woods and moved forward across the road into the open. I saw at once that they had four or five to my one. The First Brigade was at once faced about (I presume by General Winthrop’s order) and marched back across the field in good order. I expected to form my lines along the southern line of the field and fight it out, but the supports could not be held.”

The reality was that Ayres’ Division had been hit front and flank very unexpectedly and had disintegrated, running for the lines of Crawford’s supporting Third Division. First Brigade commander Brigadier General Joseph Hayes gave a similar account of the action in this first phase of the battle:

“At 11 a. m., the order to advance being received, the brigade promptly moved to the attack. The enemy were at this time concealed along the White Oak road, and there was nothing to indicate either their number or position excepting the heavy fire with which they greeted our line as it advanced. Through this fire, over an open field for one-quarter of a mile, the brigade charged with unwavering and unbroken front. On reaching within ten or fifteen yards of the enemy’s position two lines of battle, rising from their ambush, were hurled upon the thin and already weakened single line of this brigade. To have attempted to hold the ground would have exposed the command to capture by vastly superior numbers; the order was accordingly given to face about, and the brigade retired to its former position. Subsequently the line was established along Gravelly Run…”

This assault happened so quickly that Crawford’s trailing Third Division had scarcely more time to react, being hampered in its efforts by the fleeing men of Ayres’ Division. Brigadier General Richard Coulter’s Third Brigade of Crawford’s Division had been ordered to Ayres that morning. He recalled the sudden fury of the Confederate attack:

“By orders from division headquarters reported to General Ayres, and was shown position to be occupied by brigade, short distance in rear of Second Division lines. While going into position right by file preceding line had advanced and engaged enemy, and before this brigade was, or could be, properly in position first line was retiring. Pressed by the enemy about same time, of four battalions in position, three of the commanders – Lieutenant-Colonel Dailey, One hundred and forty-seventh New York, Lieutenant-Colonel Warren, One hundred and forty-second Pennsylvania Volunteers, and Major Fish, Ninety-fourth New York – had been wounded. The enemy had also concentrated a fire on left flank. These causes, with the retiring of Second Division, compelled the falling back of this brigade. After several temporary intermediate formations of line, secured position on ridge occupied by First Division (General Griffin).”

Kellogg’s First Brigade of Crawford’s Division was called upon to halt the rout. Kellogg deployed the 6th Wisconsin and 7th Wisconsin, famous regiments of the Iron Brigade, to stem the rout. But two regiments were no match for the body of men rushing for the rear. The Wisconsin men were pushed aside and forced to join the retrograde movement.

The Confederates bagged many prisoners in this initial assault. Warren’s Fifth Corps suffered 464 missing this day, many of them in Ayres’ Second Division. The Confederates caused an unexpected minor disaster, but Lee soon realized this was a hollow victory. Only three of his four brigades (Wise was held in reserve) had attacked, and they would be in an exposed position close to the Union lines if they advanced. Content with the current gains, the Confederate commander gathered up his prisoners and had the motley though victorious attacking force reverse some fortifications Warren’s men had dug earlier. In this way they might still keep Warren off of the all-important White Oak Road. Though badly shaken, the divisions of Ayres and Crawford had escaped a more serious reverse due to the protective cover of Gravelly Run, Griffin, and Wainwright’s Fifth Corps artillery.

The Confederate decision to call off the attack and entrench created a pause in the battle during the early afternoon hours. Grant was less than pleased when informed of the result, asking Meade why Warren fought his divisions in detail. He reasoned to Army of the Potomac’s comander that since the Confederates had come out of their intrrenchments to attack, they were now vulnerable and should be counterattacked immediately. Warren and his division commanders had more pressing issues to worry about than Grant’s displeasure. They feverishly worked to reorganize the Second and Third divisions in case of further assaults. Griffin’s First Division, which had held behind the branch of Gravelly Run and provided a rallying point for their comrades, would lead the afternoon counterattack. Ayres and Crawford would provide cover for his left and right flanks, respectively. Miles’ Division from Humphreys’ Second Corps would pitch in to the right of the Fifth Corps.

The attack, led by Joshua L. Chamberlain’s Brigade, just like at Lewis’ Farm on March 29, was launched around mid-afternoon. After wavering for just a moment due to Confederate artillery fire, the Federal assault routed the Confederate defenders and drove them back into their original works along the White Oak Road, capturing most of the 56th Virginia. More importantly, Chamberlain’s Brigade moved across White Oak Road, cutting the direct Confederate connection with Pickett at Five Forks. Chamberlain’s official report gives the details:

“I was desired by General Griffin to regain the field which these troops had yielded. My men forded a stream nearly waist deep, formed in two lines, Major Glenn having the advance, and pushed the enemy steadily before them. Major-General Ayres’ division supported me on the left in echelon by brigade, the skirmishers of the First Division, in charge of General Pearson, in their front. We advanced in this way a mile or more in to the edge of the field it was desired to retake. Up to this time we had been opposed by only a skirmish line, but quite a heavy fire now met us, and a line of battle could be plainly seen in the opposite edge of woods and in a line of breast-works in the open field, in force at least equal to our own. I was now ordered by Major-General Warren to halt and take the defensive. My first line had now gained a light crest in the open field, where they were subjected to a severe fire from the works in front and from the woods on each flank. As it appeared that the enemy’s position might be carried with no greater loss than it would cost us merely to hold our ground, and the men were eager to charge over the field, I reported this to General Griffin, and received permission to renew the attack. My command was brought into one line and put in motion. A severe oblique fire on my right, together with the artillery which now opened from the enemy’s works, caused the One hundred and ninety-eighth to waver for a moment. I then requested General Gregory, who reported to me with his brigade, to move rapidly into the woods on our right by battalion in echelon by the left, so as to break this flank attack, and possibly to turn the enemy’s left at the same moment that i should charge the works directly in rout at a run. This plan was so handsomely executed by all that the result was completely successful. The woods and the works were carried, with several prisoners and one battle-flag, and the line advanced some 300 yards across the White Oak road.”

Chamberlain’s cutting of the White Oak Road had major consequences for the April 1, 1865 Battle of Five Forks. Lee attempted to reinforce Pickett’s expeditionary force, but he had to send them north of Hatcher’s Run from the White Oak Road to the South Side Railroad at Sutherland’s Station, only then moving southwest to Five Forks. Despite the Fifth Corps mostly having moved on the night of March 31 to Sheridan’s aid at Dinwiddie Court House, Lee’s reinforcements took the more roundabout route and never arrived in time.

Though victorious at White Oak Road, the Federals had a potentially large problem on their hands on the late afternoon of March 31. A combined infantry/cavalry force under George Picket and Fitz Lee surprised and drove Sheridan’s Cavalry back almost to Dinwiddie Court House, in the left rear of Warren’s Fifth Corps. When it was realized that Pickett was severely pressing Sheridan’s cavalry force near Dinwiddie Court House to the southwest, Warren sent Bartlett’s Brigade to attempt a flank attack on Pickett’s Confederates. For more on the operations around Dinwiddie Court House on March 31, click here to read my post on that fight.

The night of March 31 would see Warren receive a slew of contradictory orders from Meade, Grant, and Sheridan, all trying to get some infantry support for the beleaguered Sheridan. Warren’s actions, or lack of perceived action, would cost him dearly very soon. The Battle of Five Forks, and a day later the final assaults on Petersburg, lay in the near future.

Stay tuned for the final struggles…

Further Reading:

- History and Tour Guide of Five Forks: Hatcher’s Run and Namozine Church by Chris Calkins, pages 42-54

- The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion by A. Wilson Greene, pages 169-174

- The Petersburg Campaign Volume II: The Western Front Battles September 1864-April 1865 by Ed Bearss, edited by Bryce Suderow, pages 405-436

- In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat by Earl J. Hess, pages 258-260

- The Petersburg Campaign June 1864-April 1865 by John Horn, pages 219-229

- The Battle of Five Forks by Ed Bearss and Chris Calkins

- Jim Epperson’s Five Forks Campaign Page

- History and Tour Guide of Five Forks, Hatcher’s Run and Namozine Church by Chris Calkins

- 150 Years Ago Today at Petersburg: March 31, 1865

- 150 Years Ago Today: The Battle of White Oak Road: March 31, 1865

- Actions Around Petersburg Wikipedia Map: March 29-April 1, 1865

- Book Review: Through Blood and Fire: The Civil War Letters of Major Charles J. Mills, 1862-1865 edited by J. Gregory Acken

- CLARK NC: 27th North Carolina at the Siege of Petersburg

- Early Thoughts on Confederate Waterloo

- G. K. Warren’s Downfall: How the Battles of Quaker Road and White Oak Road Cost Warren His Job

- History and Tour Guide of Five Forks, Hatcher’s Run and Namozine Church by Chris Calkins

- The Last Campaign of the War: Albert Stickney’s Unpublished Five Forks Manuscript, Chapter 1

- LT: March 31, 1865 Robert E. Lee

- LT: March 31, 1865 Theodore Lyman

- MAP: Map of the Battlefield of Five Forks, VA. April 1st 1865 and of Field of Operation Preliminary to It Showing the Operations of the Fifth Army Corps Commanded by Maj. Gen. G. K. Warren (Chamberlain, Passing of the Armies)

- MAP: Area of Boydton Plank Road and Hatcher’s Run: March 1865 (Lyman Letters)

- MHSM Papers V6: Operations of the Fifth Corps on the Left, March 29 to Nightfall March 31, 1865: Gravelly Run

- MOLLUS ME V1: The Military Operations on the White Oak Road, Virginia, March 31, 1865 by Brevet Major-General Joshua L. Chamberlain

- MOLLUS ME V2: Five Forks by Joshua L. Chamberlain

- MOLLUS WI V1: Assault on the Lines of Petersburg, April 2, 1865 by Charles H. Anson

- NP: April 3, 1865 Richmond Examiner: Operations on the Southside, March 28-31, 1865

- NP: December 6, 1945 Baldwinsville NY Messenger: 185th New York at Petersburg, Part 5

- NP: April 1, 1965 Petersburg Progress-Index: Siege Centennial, Part 39: Five Forks: Signal For Evacuation

- NT: November 10, 1898 National Tribune: The Pennsylvania Reserves from Cold Harbor to Appomattox

- OR LI P1: Report of Colonel Richard N. Batchelder, Chief Quartermaster, AotP, June 30, 1864 – June 30, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #1: Report of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding U.S. Army, March 1864-May, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #4: Itineraries of the Army of the Potomac, Sheridan’s Cavalry Command, and the Army of the James, January-April 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #92: Report of Surg. T. Rush Spencer, Medical Director, V/AotP, Feb 5-Apr 30, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #4: Report of Major General George G. Meade, commanding Army of the Potomac, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #6: Report of Surg. Thomas A. McParlin, Medical Director, Army of the Potomac, Jan 1-Jun 30, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #7: Report of Surg. John A. Lidell, Inspector of Medical and Hospital Dept, Army of the Potomac, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #21: Reports of Major General Andrew A. Humphreys, commanding II/AotP, March 29-April 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #23: Reports of Asst. Surg. Charles Smart, Medical Inspector, II/AotP, Mar 1-Apr 30, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #24: Report of Captain John G. Pelton, 14th CT, Chief of Ambulances, II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #25: Reports of Bvt. Major General Nelson A. Miles, commanding 1/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #26: Report of Colonel George W. Scott, 61st NY, commanding 1/1/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #27: Report of Captain Lucius H. Ives, 26th MI, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #28: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Welcome A. Crafts, 5th NH, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #30: Report of Major George W. Schaffer, Sixty-first New York Infantry, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #31: Report of Captain William A. F. Stockton, 140th PA, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #32: Report of Colonel Robert Nugent, 69th NY, commanding 2/1/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #34: Report of Captain William H. Terwilliger, 63rd NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #35: Report of Lieutenant Colonel James J. Smith, 69th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #36: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Denis F. Burke, 88th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #37: Report of Major Seward F. Gould, 4th NYHA, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #38: Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Clinton D. MacDougall, 111th NY, commanding 3/1/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #39: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Pokorny, 7th NY (Veteran), Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #40: Report of Major John McE. Hyde, 39th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #41: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Henry M. Karples, 52nd NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #42: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Lewis W. Husk, 111th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #43: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Hyde, 125th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #44: Report of Captain I. Hart Wilder, 126th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #45: Report of Bvt. Brigadier General John Ramsey, 8th NJ, commanding 4/1/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #46: Report of Lieutenant Colonel William Glenny, 64th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #47: Report of Captain Nathaniel P. Lane, 66th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #48: Report of Colonel William M. Mintzer, 53rd PA, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #49: Report of Captain John R. Weltner, 116th PA, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #51: Report of Captain John F. Sutton, 148th PA, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #67: Report of Brigadier General Regis de Trobriand, commanding 3/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #68: Report of Brigadier General Regis de Trobriand, commanding 1/3/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 6, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #72: Report of Bvt. Lieutenant Colonel John G. Hazard, 1st RI Lt Arty, commanding Arty/II/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #74: Reports of Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, commanding V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #76: Report of Asst. Surg. Charles K. Winne, Medical Inspector, V/AotP, Mar 26-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #77: Report of Bvt. Major General Charles Griffin, commanding 1/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #78: Report of Brigadier General Joshua L. Chamberlain, commanding 1/1/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #79: Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Edgar M. Gregory, 91st PA, commanding 2/1/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #80: Reports of Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Myers, 187th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #81: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Doolittle, 188th NY, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #85: Report of Captain George R. Abbott, 1st ME SS Bn, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #91: Reports of Bvt. Major General Romeyn B. Ayres, commanding 2/V/AotP, Mar 30-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #92: Reports of Brigadier General Joseph Hayes, commanding 1/2/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #93: Reports of Colonel David L. Stanton, 1st MD, commanding 2/2/V/AotP, Mar 31-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #94: Reports of Bvt. Brigadier General James Gwyn, 118th PA, commanding 3/2/V/AotP, Mar 31-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #96: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Edward L. Witman, 210th PA, Mar 31-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #98: Reports of Colonel John A. Kellogg, 6th WI, commanding 1/3/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #99: Report of Colonel Jonathan Tarbell, 91st NY, Mar 29-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #101: Report of Lieutenant Colonel Rouse S. Egelston, 97th NY, Mar 29-Apr 1, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #102: Report of Colonel Thomas F. McCoy, 107th PA, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #103: Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Richard Coulter, 11th PA, commanding 3/3/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #104: Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Charles S. Wainwright, 1st NY Lt Arty, commanding Arty/V/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #208: Report of Major General George Crook, commanding 2/Cav/AotP, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #267: Reports of General Robert E. Lee, commanding Army of Northern Virginia, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- OR XLVI P1 #273: Report of Major General Bushrod R. Johnson, commanding Johnson/Fourth/ANV, Mar 29-Apr 9, 1865

- Position of the Fifth Corps at 10:30 am on March 31, 1865 (Official Records)

- The Battle of White Oak Road CWPT Map

- The Battle of White Oak Road: March 31, 1865

- The Battle of White Oak Road: March 31, 1865 (Maine MOLLUS Vol. 1)

- The Battle of White Oak Road NPS Map: Aftermath

- The Battle of White Oak Road NPS Map: March 31, 1865 Afternoon

- The Battle of White Oak Road NPS Map: March 31, 1865 Morning

- The Battle of White Oak Road NPS Map: Prelude

- Union Casualties in the Appomattox Campaign: March 28-April 9, 1865