March 29, 1865: Grant’s Ninth Offensive Begins

Note 1: Click here for Maps of the Battle of Lewis Farm (or Quaker Road) which should help you follow along with the action.

Note 2: For an excellent first person account of the Battle of Lewis Farm (or Quaker Road), see Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain’s book, The Passing of the Armies: An Account of the Final Campaign of the Army of the Potomac, Based upon Personal Reminiscences of the Fifth Army Corps.

On March 29, 1865, 150 years ago today, the opening moves of what would be Ulysses S. Grant’s Ninth (and final) Offensive against Petersburg and Richmond kicked off, featuring a division level clash at the Battle of Lewis’s Farm (or Quaker Road) with Gettysburg hero Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain facing off against elements of Bushrod Johnson’s Confederates.

Before we get into the events of March 29, 1865, a note of reflection is in order. Ulysses S. Grant originally made plans to have the Ninth Offensive kick off before the March 25, 1865 Battle of Fort Stedman. Lee’s last grand effort at that battle, planned by Second Corps commander John B. Gordon and featuring nearly half of the remaining infantry in the Army of Northern Virginia, caused so little disruption to the Northern forces under Grant that the offensive’s starting date wasn’t even changed.

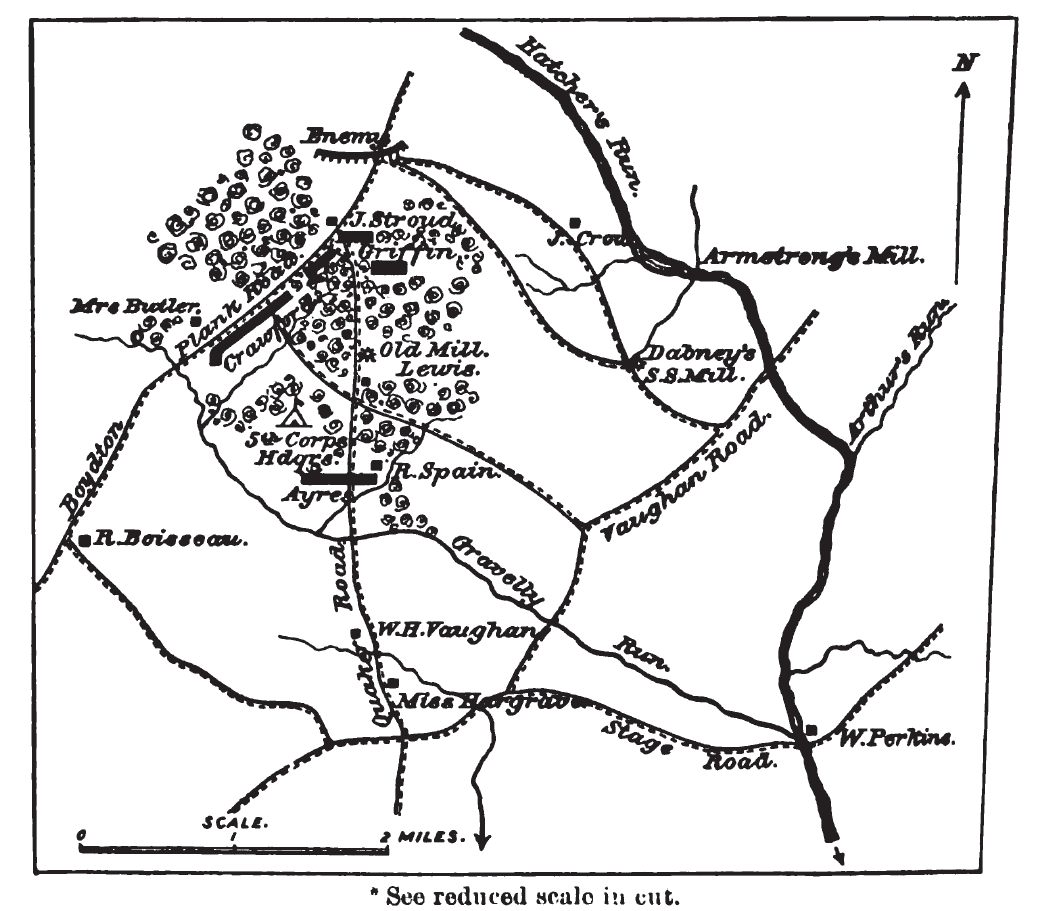

As we discussed yesterday, the movement would be made by Andrew Humphreys’ Second Corps, Gouverneur Warren’s Fifth Corps, and Philip Sheridan’s cavalry command, which consisted of the three former divisions of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps. The infantry corps would feel their way slowly northwest to develop exactly where the main line of Confederate entrenchments along the Boydton Plank Road, White Oak Road, and Hatcher’s Run were located. This line had been created to extend the Confederate presence south of Hatcher’s Run in the Burgess Mill area. The Confederates were continuing to try to protect their remaining two supply lines into Petersburg, the Boydton Plank Road and the South Side Railroad. And the Union forces were again trying to swing wide left and get astride one or both of these last two of Lee’s lifelines. One hundred and fifty years ago today, they’d cut one of them permanently.

The focus of this post will be on Gouverneur Warren’s Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac, because that’s where the main action of the day occurred. Warren’s orders had been modified the previous day, March 28, 1865, so that he wouldn’t be going in the direction of Dinwiddie Court House too soon, keeping a better connection with Second Corps and preventing a Confederate flank attack used so often during the Siege of Petersburg. Elements of Edward O. C. Ord’s Army of the James relieved Humphreys’ Second Corps troops from manning the permanent fortifications which had been created to Hatcher’s Run during the Eight Offensive in early February 1865. Humphreys, freed from his trenches due to Ord’s men, would be located to Warren’s northeast. The Second Corps commander’s instructions called for him to cross Hatcher’s Run at the Vaughan Road and then move in a northwesterly direction, resting his right on the run and his left on the Quaker Road. Warren would cross Rowanty Creek at the Perkins House on a pontoon bridge, the same crossing spot he had used during the Eighth Offensive, which put his forces south of Gravelly Run. He would proceed westward, moving parallel to that waterway down the Monks’ Neck Road, and then on to the Vaughan Road. Warren would proceed only to the Vaughan Road’s intersection with the Quaker Road, and stop to wait for word from Humphreys. Once Humphreys was in position, Warren could then proceed to the Boydton Plank Road and move northeast without there being too large of a gap between the two corps at any given point in time. If everything went according to plan, Warren would connect with Humphreys somewhere north of Gravelly Run, forming a solid line and keeping the Confederates occupied as Sheridan’s cavalry force moved to Dinwiddie Court House and beyond.

The problem was that Army of the Potomac commander George G. Meade threw a monkey wrench into the plan. At 10:20 a.m., Meade instructed Warren to move north up the Quaker Road to its intersection with Gravelly Run, rather than proceeding further west to the Boydton Plank Road. Shortly thereafter, Meade gave Warren orders to cross Gravelly Run using the Quaker Road. This meant that rather than advancing northeast up the Boydton Plank Road, his Fifth Corps would head almost due north in the direction of Hatcher’s Run and White Oak Road. Warren appears to have been confused by this last minute change in orders. To make matters worse, the bridge across Gravelly Run was out, and time was required to repair it.

After this issue, the Fifth Corps moved north up the Quaker Road, intending to follow it to its junction with the Boydton Plank Road. But they wouldn’t make it without Confederate resistance. Richard H. Anderson’s Fourth Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, essentially Bushrod Johnson’s Division and some artillery, were manning the Confederate works south of Hatcher’s Run along White Oak Road, their left southeast of Burgess Mill and their right terminating just past the Claiborne Road, both flanks firmly anchored on the run itself. Their problem was that there wasn’t enough infantry in Lee’s army to man the entrenchments from northeast of Richmond all the way down Boydton Plank Road to Dinwiddie Court House. This left the Boydton Plank Road southwest of Johnson’s line of entrenchments vulnerable, and Warren’s Union Fifth Corps was about to exploit that vulnerability.

Unit Placement Solely Based on Original Map Found in

The Petersburg Campaign, Volume II: The Western Front Battles

by Ed Bearss and Bryce Suderow, p. 343

Bushrod Johnson couldn’t sit still and allow what was as yet an unknown Union force take the Boydton Plank Road without a fight. On this day, after discovering the Yankee advance, he sent Henry Wise’s Brigade of Virginians south of his entrenchments, the 34th Virginia detached to the west to support a small cavalry force picketing the intersection of the Boydton Plank Road and the lesser used Boisseau Road. Wise was stationed near a saw mill just north of the Lewis Farm in order to protect the critical Boydton Plank Road from capture. The brigades of Ransom, Wallace, and Moody followed Wise south out of their entrenchments.

Gettysburg hero Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, just recovered from his severe wounding at the June 18, 1864 Second Battle of Petersburg, was leading Warren’s advance north up the Quaker Road with his First Brigade of Griffin’s First Division, Fifth Corps. In what was a decided rarity at this point in the war, Chamberlain’s Brigade consisted of only two large regiments, the 185th New York and the 198th Pennsylvania. Both regiments were barely six months old, both formed in September 1864, moved to the Siege of Petersburg late that month, and then brigaded together shortly in early October. Gregory’s 2nd Brigade would provide Chamberlain with support should he need it. As Chamberlain moved north up the Quaker Road, he found Wise’s men in his path. A battle would soon erupt for control of the Lewis Farm area.

In the late afternoon, probably before 4 pm, a battalion of the 198th Pennsylvania under the command of Major Glenn acting as Chamberlain’s skirmishers, ran into Wise’s Brigade posted in the woods north of the Lewis Farm on both sides of the Quaker Road. As a result Chamberlain moved his main line up close to his skirmishers as close support . The remaining battalion of the 198th Pennsylvania under Bvt. Brigadier General Sickel formed the right of Chamberlain’s main line, and the 185th New York the left, the regiments divided by the Lewis farm house. Battery B, 4th U. S. Artillery was unlimbered in the vicinity of the Lewis Farm house in the center of the Union line, a section on either side building.

First Division commander Griffin soon ordered Chamberlain forward around 4 pm, and Chamberlain’s brigade surged toward the woods, unsuccessfully trying to avoid heavy enemy fire before reaching the relative shelter of the trees. Chamberlain steadily pushed back Wise’s Brigade for a time, moving well into the woods, before Confederate resistance suddenly stiffened. This resistance soon turned into an advance, as Bushrod Johnson had ordered Wallace’s South Carolina Brigade and Moody’s Alabama Brigade in on the Virginians’ right and left flank, respectively. This Confederate assault drove Chamberlain’s men all the way back to the Lewis Farm onto the supporting artillery of Battery B, 4th U. S. Artillery.

Faced with this unexpected Confederate assault, Chamberlain’s right showed signs of buckling, but heroic efforts by Bvt. Brigadier General Sickel and Chamberlain himself caused the 198th Pennsylvania to solidify and hold. These efforts came at a high price, however, as Chamberlain and Sickel were wounded here. The Confederate attack continued to press at Chamberlain’s men, and his left flank regiment, the 185th New York, soon was flanked and collapsed, falling back to a position parallel to the Quaker Road facing west. Chamberlain called for reinforcements while this was occurring.

Around 6 pm, First Division commander Charles Griffin responded quickly, sending three regiments of the Third Brigade (155th Pennsylvania, 1st Michigan, and 16th Michigan) from directly behind Chamberlain’s embattled forces. In addition, Second Brigade commander Gregory was asked for help and sent one regiment, the 188th New York, which went in on Chamberlain’s left, flanking the Confederates in turn. This flank attack and the head-on assault by the Third Brigade regiments broke the Confederates, who finally fell back in disorder through the darkening woods to the north of the Lewis Farm. The Federals were left in control of the field as the Confederate brigades, realizing they faced a large Union force, were pulled back into the main entrenchments along White Oak Road.

Position of the Fifth Corps on the Night of March 29, 1865 (Official Records)

This last was an important development. The Confederate withdrawal left the way open to the Boydton Plank Road and the Fifth Corps took advantage. After the remainder of Griffin’s First Division and Crawford’s Second Division were fully up and consolidated, the Federals slowly pushed forward in the darkness to and just beyond the Boydton Plank Road. The Fifth Corps dug in on the spot, consolidating gains and preparing for further advances against the White Oak Road line as well. Lee’s second last supply line had been permanently cut. Only the South Side Railroad remained and it too would soon be under assault. Ayres’ Division remained behind at the Quaker Road crossing of Gravelly Run making sure that important point continued to be held. Casualties had been fairly large for a fight which saw less than a division engaged each. Both forces lost in the neighborhood of 400 men, with Chamberlain bearing the brunt of those losses on the Union side.

Robert E. Lee realized by this point that the Federals were finally mounting their long awaited Spring offensive, and he acted quickly on the morning of March 29 to move troops around to counter the threat. He sent Hunton’s Brigade of Pickett’s Division from Richmond to Petersburg. In addition, George Pickett and his other three brigades, were sent by rail to Sutherland’s Station, and were to then march to Five Forks and meet three of Lee’s cavalry divisions. reacting to what Lee knew would be more Union forces coming from the direction of Dinwiddie Court House. The fight at Lewis Farm also caused Lee to strengthen Bushrod Johnson’s White Oak Line, sending Samuel McGowan’s South Carolinians, MacRae’s North Carolinians, and Willie Pegram’s Battalion of artillery to the area.

Initially, Grant had planned to have Sheridan’s Cavalry move off on a longer distance raid around Lee’s right, trying to cut the South Side and Danville railroads well away from the main Confederate army. The success of March 29, however, caused Grant to sense blood and move in for the kill. His orders to Sheridan changed to find Lee’s right and try to get on its flank astride the South Side Railroad. Warren’s Fifth Corps and Humphreys’ Second Corps would continue to probe the Confederates south of Hatcher’s Run, looking for signs of weakness. We are in the final days of this Sesquicentennial countdown. Get ready for non-stop action until the fall of Richmond and Petersburg.

Further Reading:

- History and Tour Guide of Five Forks, Hatcher’s Run and Namozine Church by Chris Calkins, pages 36-42

- The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion by A. Wilson Greene, pages 155-158

- The Petersburg Campaign Volume II: The Western Front Battles September 1864-April 1865 by Ed Bearss, edited by Bryce Suderow, pages 310-347

- In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat by Earl J. Hess, pages 255-257

- The Petersburg Campaign June 1864-April 1865 by John Horn, pages 219-221

- The Passing of the Armies: An Account of the Final Campaign of the Army of the Potomac, Based upon Personal Reminiscences of the Fifth Army Corps by Joshua L. Chamberlain

- 198th PA: History of the One Hundred and Ninety-Eighth Pennsylvania Volunteers by E. M. Woodward, pages 36-39

- The Battle of Lewis’s Farm: March 29, 1865

- The Battle of Quaker Road Christopher Maes Charge! Map, March 29, 1865

- The Battle of Quaker Road NPS Map: Aftermath

- The Battle of Quaker Road NPS Map: March 29, 1865

- The Battle of Quaker Road NPS Map: Prelude

- Charge! Issue 13, Page 16: Lewis’s Farm (Quaker Road) by Christopher Maes

- The Last Campaign of the War: Albert Stickney’s Unpublished Five Forks Manuscript, Chapter 1

- G. K. Warren’s Downfall: How the Battles of Quaker Road and White Oak Road Cost Warren His Job

- MHSM Papers V6: Operations of the Fifth Corps on the Left, March 29 to Nightfall March 31, 1865: Gravelly Run

- Number 74. Appomattox Reports of Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, U. S. Army, commanding Fifth Army Corps

- Number 76. Appomattox Report of Asst. Surg. Charles K. Winne, U. S. Army, Medical Inspector

- Number 77. Appomattox Report of Bvt. Major General Charles Griffin, U. S. Army, commanding First Division

- Number 78. Appomattox Report of Brigadier General Joshua L. Chamberlain, U. S. Army, commanding First Brigade

- Number 79. Appomattox Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Edgar M. Gregory, Ninety-first Pennsylvania Infantry, commanding Second Brigade

- Number 80. Appomattox Reports of Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Myers, One hundred and eighty-seventh New York Infantry

- Number 81. Appomattox Report of Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Doolittle, One hundred and eighty-eighth New York Infantry

- Number 85. Appomattox Report of Captain George R. Abbott, First Maine Sharpshooters

- Number 98. Appomattox Reports of Colonel John A. Kellogg, Sixth Wisconsin Infantry, commanding First Brigade

- Number 99. Appomattox Report of Colonel Jonathan Tarbell, Ninety-first New York Infantry

- Number 101. Appomattox Report of Lieutenant Colonel Rouse S. Egelston, Ninety-seventh New York Infantry

- Number 102. Appomattox Report of Colonel Thomas F. McCoy, One hundred and seventh Pennsylvania Infantry

- Number 103. Appomattox Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Richard Coulter, Eleventh Pennsylvania Infantry, commanding Third Brigade

- Number 104. Appomattox Report of Bvt. Brigadier General Charles S. Wainwright, First New York Light Artillery, commanding Artillery Brigade